| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Original Article

Volume 10, Number 2, February 2018, pages 117-124

Effect of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor/Calcium Antagonist Combination Therapy on Renal Function in Hypertensive Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: Chikushi Anti-Hypertension Trial - Benidipine and Perindopril

Tetsu Okudaa, b, Keisuke Okamuraa, Kazuyuki Shiraia, Hidenori Urataa

aDepartment of Cardiovascular Disease, Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital, 1-1-1, Zokumyoin, Chikusino-shi, Fukuoka 818-8502, Japan

bCorresponding Author: Tetsu Okuda, Department of Cardiovascular Disease, Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital, 1-1-1, Zokumyoin, Chikusino-shi, Fukuoka 818-8502, Japan

Manuscript submitted November 4, 2017, accepted November 23, 2017

Short title: CHAT-BP

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr3253w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Appropriate blood pressure control suppresses progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). If an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor is ineffective, adding a calcium antagonist is recommended. We compared the long-term effect of two ACE inhibitor/calcium antagonist combinations on renal function in hypertensive patients with CKD.

Methods: Patients who failed to achieve the target blood pressure (systolic/diastolic: < 130/80 mm Hg) with perindopril monotherapy were randomized to either combined therapy with perindopril and the L-type calcium antagonist amlodipine (group A) or perindopril and the T/L type calcium antagonist benidipine (group B). The primary endpoint was the change of the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) after 2 years. Eligible patients had a systolic pressure ≥ 130 mm Hg and/or diastolic pressure ≥ 80 mm Hg and CKD (urine protein (+) or higher, eGFR < 60 min/mL/1.73 m2).

Results: After excluding 38 patients achieving the target blood pressure with perindopril monotherapy, 121 patients were analyzed (62 in group A and 59 in group B). Blood pressure decreased significantly in both groups, but there was no significant change of the eGFR. However, among patients with diabetes, eGFR unchanged in group B (n = 37, 59.1 ± 15.1 vs. 61.2 ± 27.9, P = 0.273), whereas decreased significantly in group A (n = 31, 57.3 ± 16.0 vs. 53.7 ± 16.7, P = 0.005).

Conclusions: In hypertensive patients with diabetic nephropathy, combined therapy with an ACE inhibitor and T/L type calcium antagonist may prevent deterioration of renal function more effectively than an ACE inhibitor/L type calcium antagonist combination.

Keywords: Amlodipine; Benidipine; Chronic kidney disease; Diabetes; Perindopril; Hypertension

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Many large-scale studies have demonstrated that appropriate control of blood pressure can suppress progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1] and occurrence of cardiovascular complications [2]. In CKD patients, proteinuria and a decrease of the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) are risk factors for end-stage renal failure or cardiovascular disease (CVD). It has also been reported that the risk of adverse outcomes increases as the eGFR declines or as urinary protein excretion becomes higher [3, 4].

Considering the suppression of proteinuria and preservation of renal function, first-line antihypertensive therapy for CKD patients with diabetes or proteinuria includes renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors.

However, polypharmacy is often needed in CKD patients to achieve the target blood pressure [1], with calcium (Ca) antagonists and diuretics being recommended for combination therapy. The ACCOMPLISH trial showed that the incidence of renal events was lower in patients treated with a long-acting Ca antagonist and an ACE inhibitor than in patients using a thiazide diuretic plus an ACE inhibitor [5].

Different Ca antagonists show differing effects on urine protein excretion when administered concomitantly with RAS inhibitors [6-8]. Ca antagonists that block T or N type Ca channels are recommended to decrease proteinuria. However, the influence of Ca antagonist channel selectivity on the eGFR has not been clarified and there are few trials examined in the long term [6-8].

Accordingly, we conducted a prospective, randomized, multicenter study in hypertensive patients with CKD to evaluate the long-term (2 years) effect on renal function of combined therapy with the ACE inhibitor perindopril (which has shown efficacy in many clinical studies [9, 10]) and amlodipine (an L-type Ca antagonist) versus combined therapy with perindopril and benidipine (a T/L type Ca antagonist).

| Patients and Methods | ▴Top |

Patients

This was a prospective, randomized, multicenter comparative study with a 2-year observation period in hypertensive patients with CKD. The long-term effects of perindopril/amlodipine therapy and perindopril/benidipine therapy were compared with regard to blood pressure, eGFR, urinary albumin excretion, and urine protein excretion (qualitative). Before enrolment, we fully explained the details of the study to the candidate patients, and obtained written informed consent. This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Eligible patients fitted the following enrolment criteria: 1) blood pressure ≥ 130/80 mm Hg measured at the outpatient clinic, 2) qualitative urine protein (1+) or higher or eGFR < 60 min/mL/1.73 m2, 3) age ≥ 20 years, 4) outpatients (not hospitalized), and 5) patients who provided written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) sitting systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 200 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 120 mm Hg at enrolment, 2) secondary hypertension, 3) serious cerebrovascular disease/CVD requiring hospitalization (e.g., stroke, myocardial infarction) within the previous 6 months, 4) cardiac failure (class III or IV in the NYHA functional classification), 5) severe liver dysfunction (AST or ALT ≥ 100 IU/L) or severe renal dysfunction (serum creatinine ≥ 2.0 mg/dL), 6) malignant tumor or another serious disease with a poor prognosis, 7) women who were pregnant or possibly pregnant, 8) patients with contraindications for any of perindopril, amlodipine, or benidipine, and 9) patients who were unsuitable for enrolment due to another medical reason in the opinion of the attending physician.

| Methods | ▴Top |

During the observation period, written informed consent was obtained from candidate subjects, their eligibility was confirmed, and they were enrolled in the preliminary study period. Treatment was changed to monotherapy with perindopril (4 mg/day). Blood pressure was measured at our outpatient clinic according to the JSH 2009 guideline and the target blood pressure was < 130/80 mm Hg as specified in this guideline. Patients who achieved the target blood pressure with perindopril at 4 mg/day were excluded from the main study. Patients who failed to achieve the target blood pressure after at least 4 weeks of treatment with perindopril were randomized (using a table of random numbers) to either the amlodipine group or the benidipine group by the central registration method.

Dose escalation was allowed up to the approved maximum dose when the target blood pressure was not achieved after addition of amlodipine or benidipine. Antihypertensive drugs other than RA inhibitors or Ca antagonists could be added if the target blood pressure was not achieved with the maximum dose of amlodipine or benidipine.

Discontinuation criteria were as follows: 1) patients who showed deterioration such as worsening of hypertension or complications, 2) patients who required significant modification of treatment due to an event, 3) patients in whom continuation of study treatment became difficult due to a serious adverse event, 4) patients who the investigator judged should not continue treatment, 5) patients who asked to discontinue the study, and 6) patients who changed hospital and could not continue the study.

The primary endpoint was the change of eGFR from baseline to the end of the main study. Secondary endpoints were the change of CKD stage, change of urinary albumin excretion, and change of qualitative urine protein excretion. Laboratory tests were conducted at the time of obtaining informed consent, at enrolment in the main study, and 6, 12, and 24 months after the start of study treatment. Parameters assessed were the serum creatinine level, total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, Na, K, and Cl.

The eGFR was calculated by the revised abbreviated MDRD equation specified in the evidence-based clinical practice guideline for CKD 2013 [11]: eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) = 194 × (age) - 0.287 × (serum Cr) - 1.094 (× 0.739 for women).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± SD or mean ± SE. Comparisons within or between groups were performed by the paired or unpaired t-test for data showing a normal distribution, and by the Wilcoxon test or Mann-Whitney test for other data. Categorical data were analyzed by the Chi-square test. Two-tailed P values < 0.05 were accepted as indicating significance.

| Results | ▴Top |

Study population and baseline characteristics

A total of 214 patients were enrolled in the preliminary study. The 38 patients in whom the target blood pressure was achieved by perindopril monotherapy and 55 patients who met above discontinuation criteria were excluded from the main study, and the remaining 121 patients (62 in the amlodipine group and 59 in the benidipine group) were analyzed. Patient background factors at baseline are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences of background factors between the two groups.

Click to view | Table 1. Patient Characteristics |

Effect on blood pressure

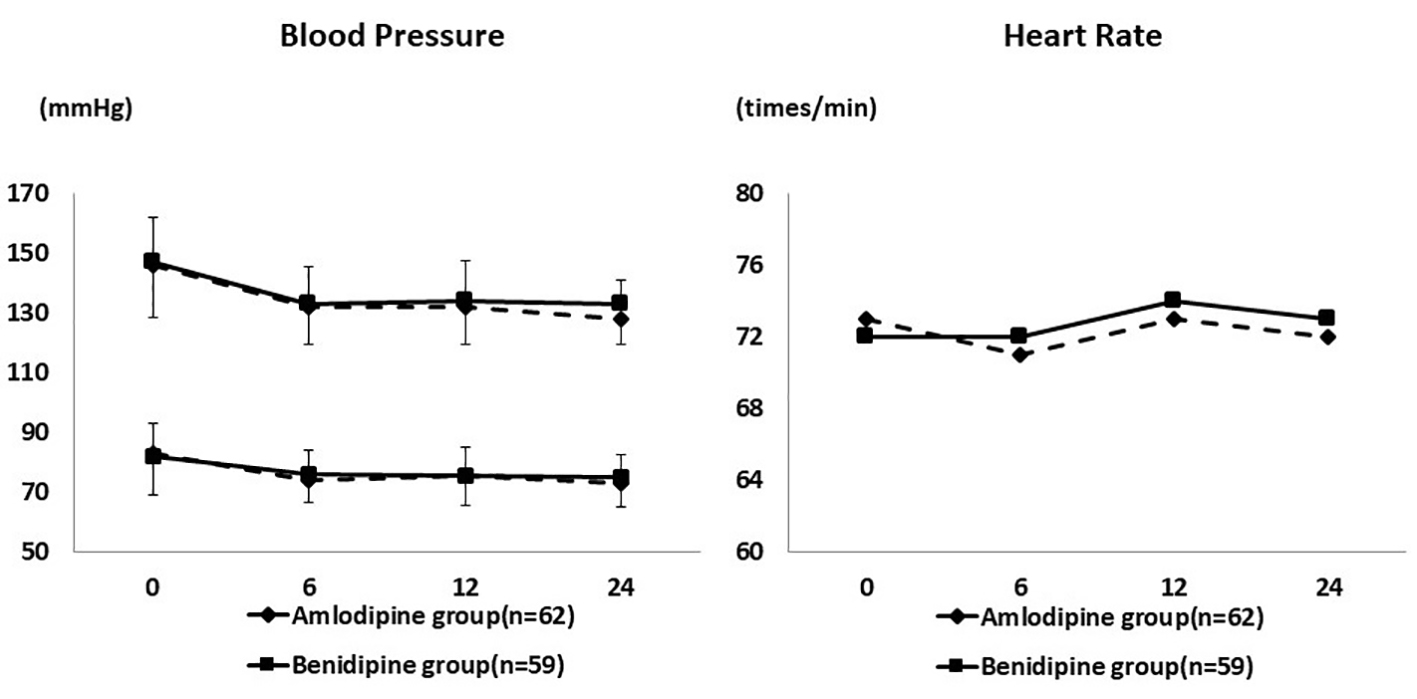

At the end of the study, the mean daily dose was 5.2 ± 2.1 mg for amlodipine and 5.3 ± 2.1 mg for benidipine. As shown in Figure 1, SBP and DBP decreased significantly from baseline after 6 months of treatment in both groups. SBP decreased from 145.8 ± 18.8 mm Hg to 128.2 ± 13.8 mm Hg in the amlodipine group and from 146.7 ± 15.6 mm Hg to 133.5 ± 12.9 mm Hg in the benidipine group. The heart rate remained at approximately the same level throughout the study period.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Changes of blood pressure and heart rate during the study period. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure decreased significantly in both groups. The heart rate remained at approximately the same level. |

Effect on the eGFR

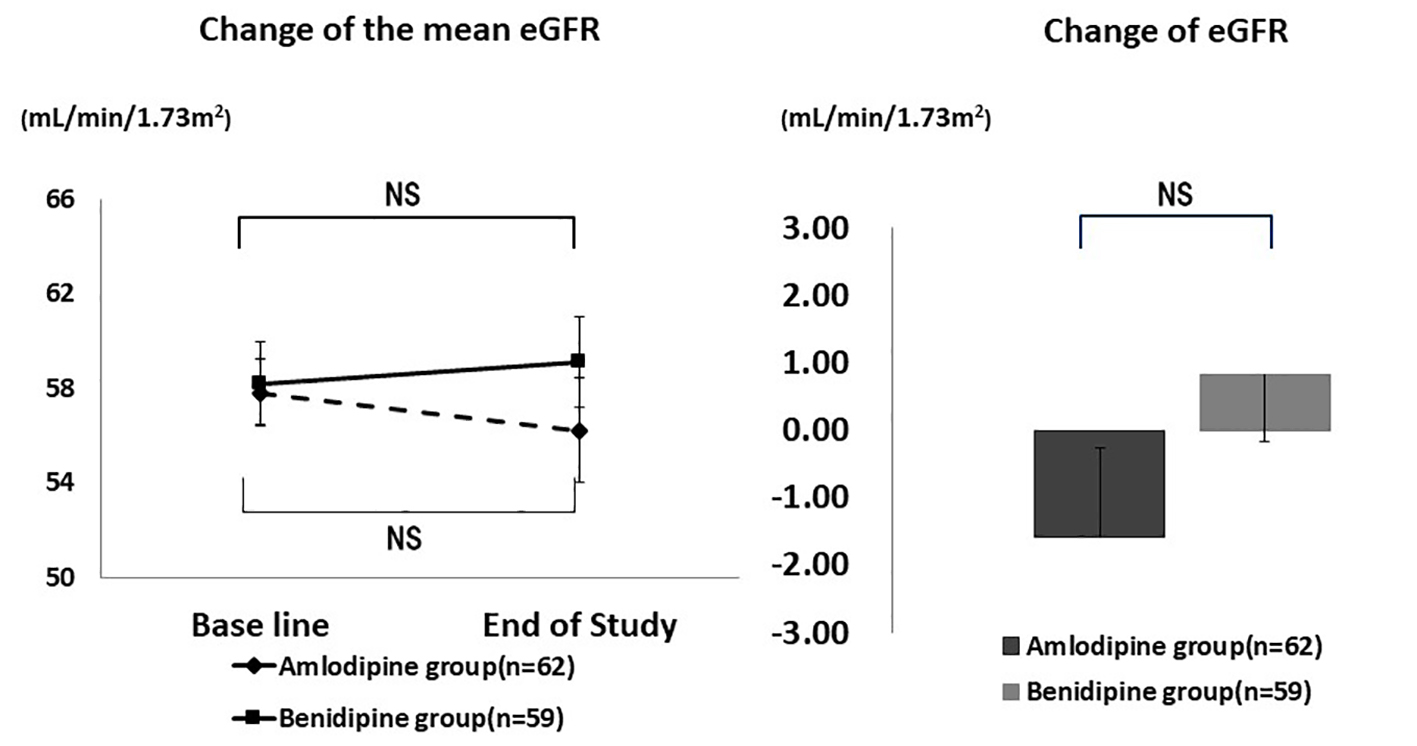

As shown in Figure 2, there was no significant change of the mean eGFR. In the amlodipine group, mean eGFR was 57.8 ± 17.2 mL/min/1.73 m2 at baseline and 56.2 ± 19.3 mL/min/1.73 m2 at the end of the study (P = 0.113), while the respective values in the benidipine group were 58.2 ± 14.4 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 59.1 ± 22.2 mL/min/1.73 m2 (P = 0.316). The change of eGFR showed no significant difference between the amlodipine group (-1.58 ± 10.1 mL/min/1.73 m2) and the benidipine group (0.83 ± 13.2 mL/min/1.73 m2) (P = 0.170).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Changes of eGFR. There was no significant difference in the mean eGFR and the change of eGFR. NS: not significant. |

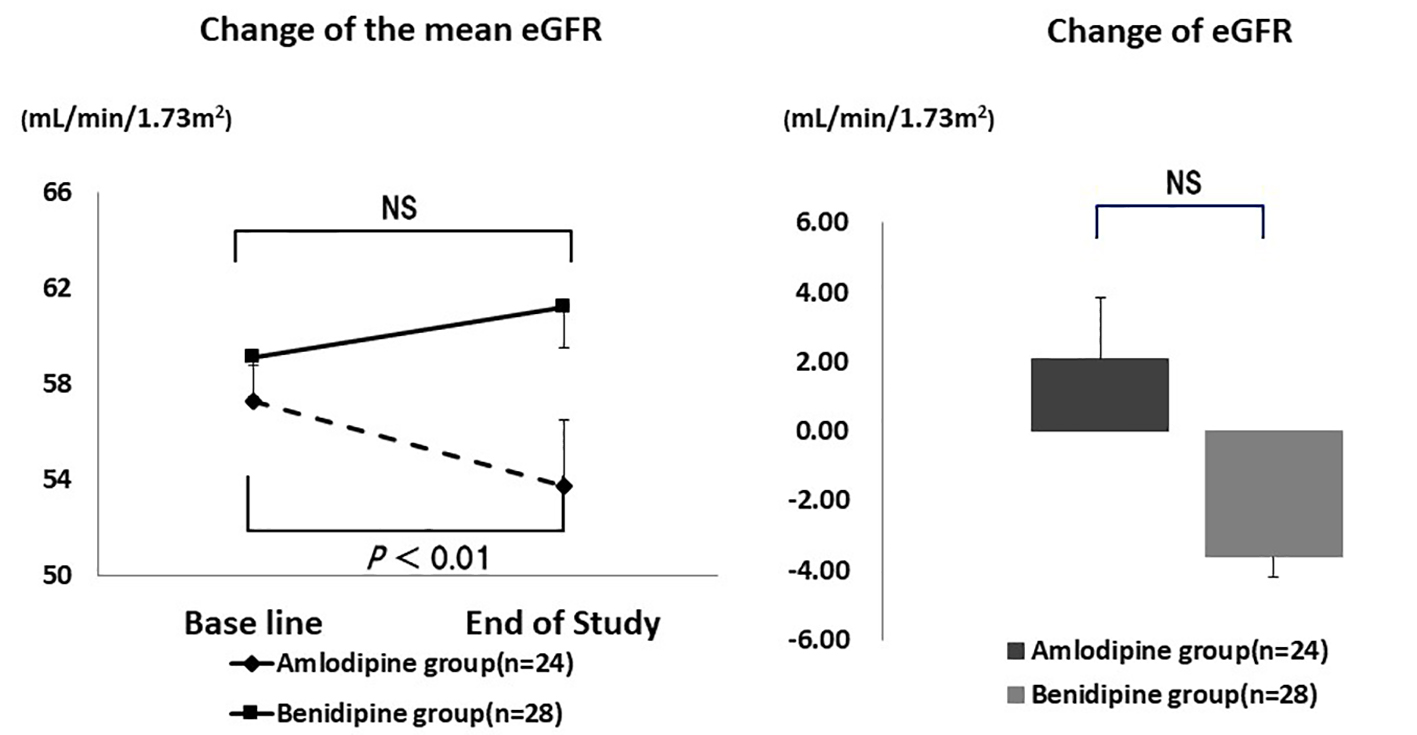

As shown in Figure 3, the mean eGFR of patients with diabetes decreased significantly by the end of the study in the amlodipine group (from 57.3 ± 16.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 to 53.7 ± 16.7 mL/min/1.73 m2, P = 0.005), but not in the benidipine group (from 59.1 ± 27.9 mL/min/1.73 m2 to 61.2 ± 37.9 mL/min/1.73 m2, P = 0.273), indicating that renal function was better preserved in the benidipine group. However, the absolute change of eGFR did not show a significant difference between the amlodipine group and the benidipine group (-3.59 ± 6.2 mL/min/1.73 m2 vs. 2.08 ± 17.7 mL/min/1.73 m2, P = 0.074).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Changes of eGFR in diabetic patients. The mean eGFR decreased significantly in the amlodipine group, but not in the benidipine group. However, there was no significant difference in the change of eGFR. NS: not significant. |

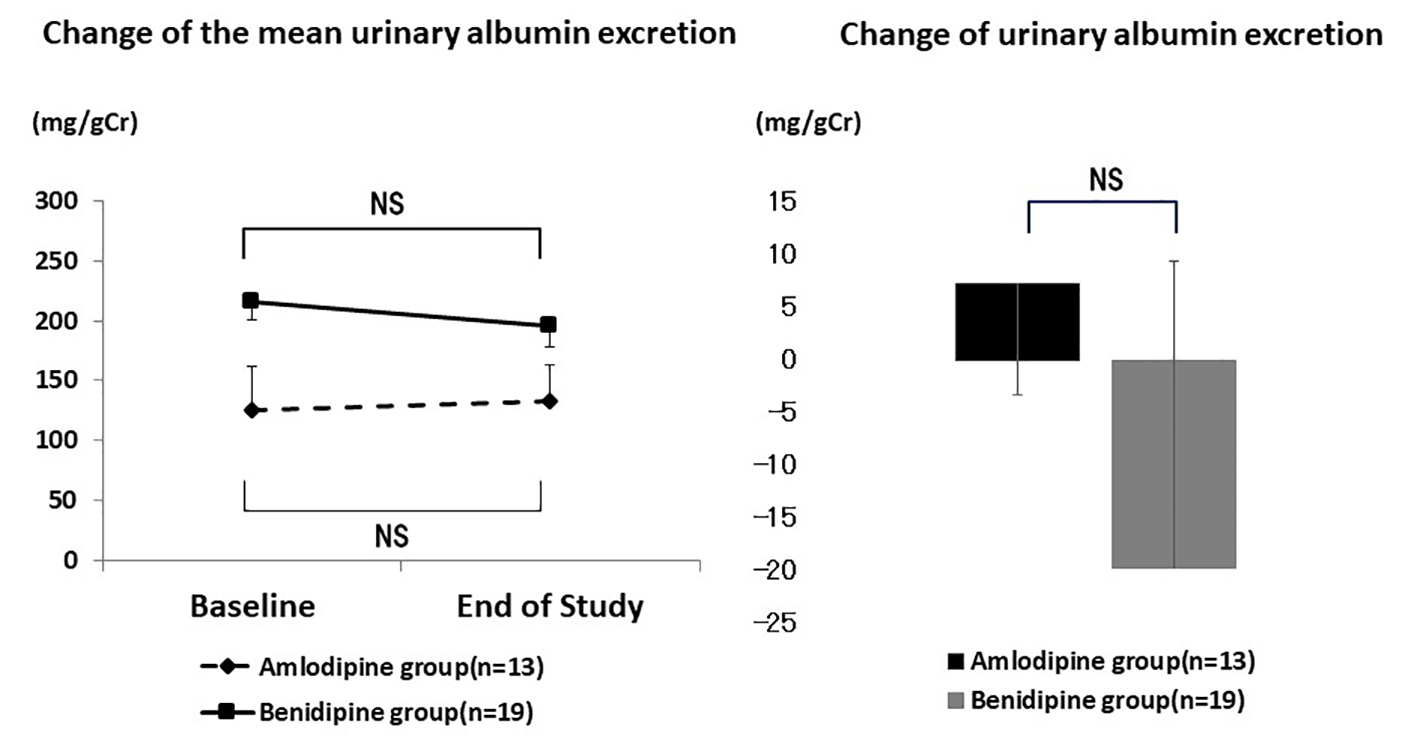

Urinary albumin excretion

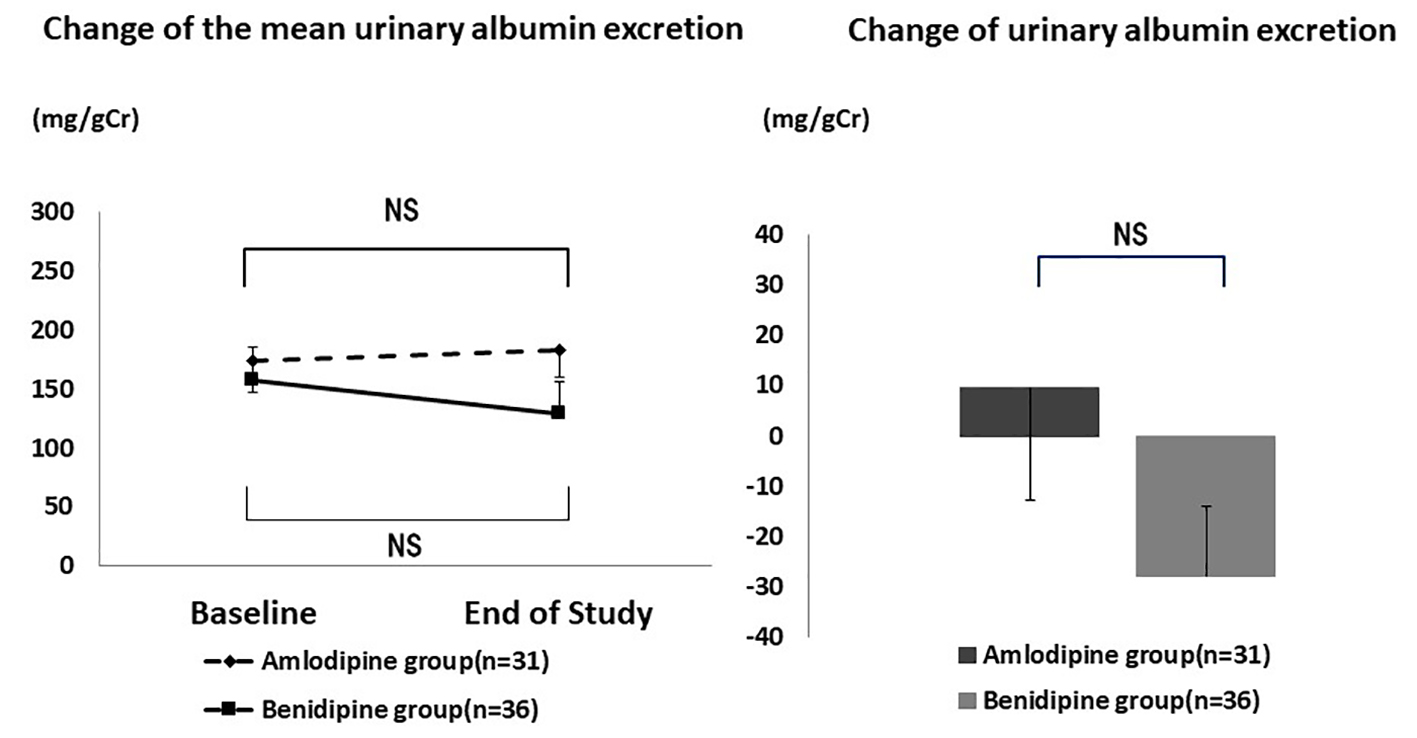

Mean urinary albumin excretion showed no significant changes during the study (Fig. 4). It was 174.0 ± 288.9 mg/gCr at baseline and 183.4 ± 272.8 mg/gCr at the end of the study (P = 0.356) in the amlodipine group, while the respective values were 157.2 ± 275.4 mg/gCr and 129.3 ± 236.3 mg/gCr (P = 0.231) in the benidipine group. The absolute change of urinary albumin excretion showed no significant difference between the amlodipine group and the benidipine group (9.4 ± 137.8 mg/gCr vs. -27.9 ± 221.5 mg/gCr, P = 0.214).

Click for large image | Figure 4. Changes of urinary albumin excretion. There was no significant difference in the mean urinary albumin excretion and the change of urinary albumin excretion. NS: not significant. |

Mean urinary albumin excretion also showed no significant change in patients with diabetes (Fig. 5). It was 125.6 ± 141.3 mg/gCr at baseline and 132.9 ± 172.0 mg/gCr at the end of the study (P = 0.408) in the amlodipine group, while the respective values in the benidipine group were 215.2 ± 360.9 mg/gCr and 306.0 ± 195.4 mg/gCr (P = 0.389). The absolute change of urinary albumin excretion also showed no significant difference between patients with diabetes in the amlodipine group and the benidipine group (7.3 ± 106.1 mg/gCr vs. -19.8 ± 292.1 mg/gCr, P = 0.379).

Click for large image | Figure 5. Changes of urinary albumin excretion in diabetic patients. There was no significant difference in the mean urinary albumin excretion and the change of urinary albumin excretion in diabetic patients. NS: not significant. |

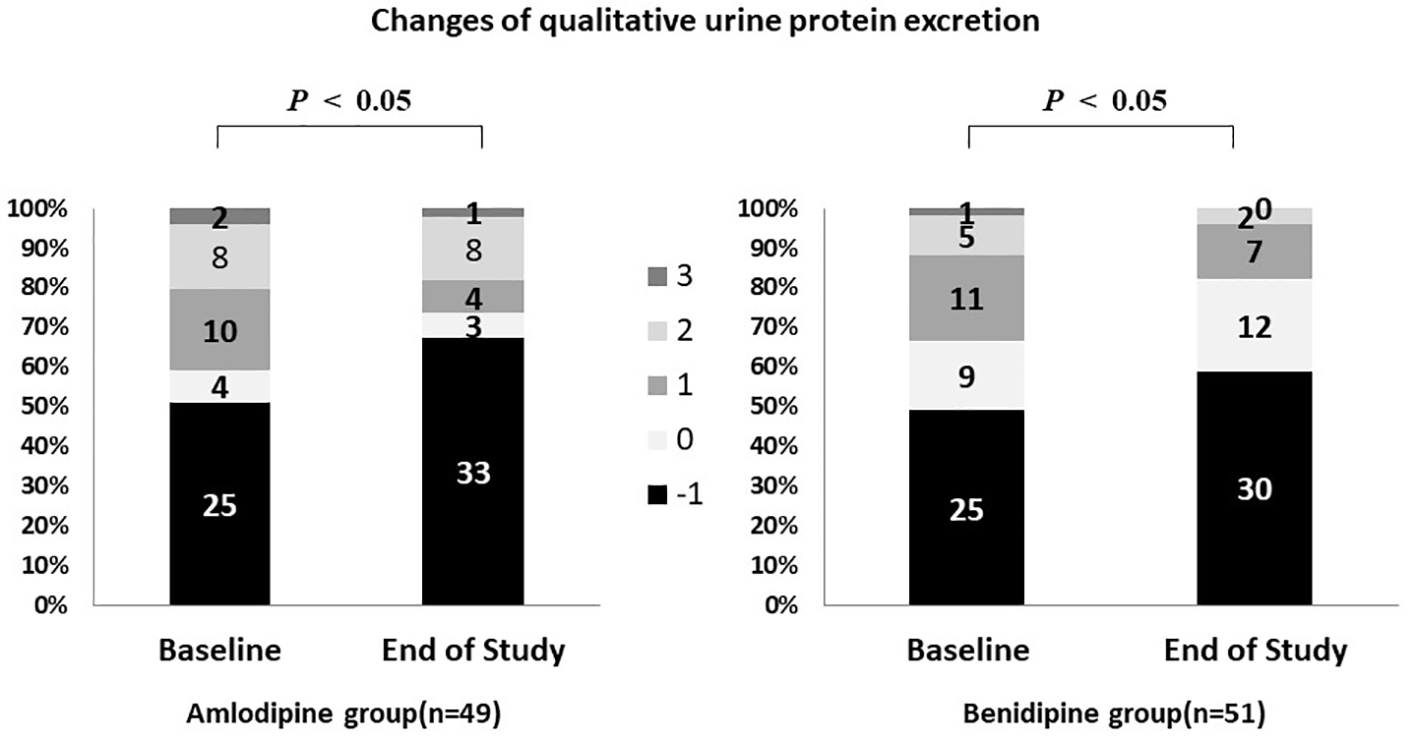

Qualitative urine protein excretion

Qualitative urine protein excretion was significantly improved in the amlodipine group (Fig. 6). It was rated as (-) in 25 patients at baseline and in 33 patients at the end of the study period, while it was rated as (±) in four and three patients, (1+) in 10 and four patients, (2+) in eight and eight patients, and (3+) in two patients and one patient, respectively (P = 0.023).

Click for large image | Figure 6. Changes of qualitative urine protein excretion. P < 0.05 vs. baseline. Qualitative urine protein excretion was significantly improved in both groups. |

Qualitative urine protein excretion also improved significantly in the benidipine group (Fig. 6). It was rated as (-) in 25 patients at baseline and in 30 patients at the end of the study period, while it was rated as (±) in nine and 12 patients, (1+) in 11 and seven patients, (2+) in five and two patients, and (3+) in one and 0 patients, respectively (P = 0.021).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In the present study (Chikushi anti-hypertension trial - benidipine and perindopril (CHAT-BP)), the primary endpoint was eGFR, which increased in the benidipine group and decreased in the amlodipine group. However, there was no significant difference of eGFR between the two groups or between baseline and the end of the study within each group.

The small sample size of this study may be the primary reason for lack of a significant between-group difference. Although the target was to enroll 200 patients in each group, eGFR was evaluable in fewer than 50 patients per group. Only benidipine group showed a slight inprove, but not significant in the eGFR, suggesting that there may have been a significant difference between the benidipine and amlodipine groups if data had been obtained from more patients.

Recently, there has been an increase of patients with hypertension, diabetic nephropathy, and renal failure, and they account for the majority of patients starting dialysis in Japan. The objective of antihypertensive therapy is to reduce the blood pressure and suppress organ damage associated with hypertension, including renal failure [12].

A meta-analysis demonstrated a renoprotective effect of RAS inhibitors and superiority compared to other antihypertensive agents in hypertensive patients with diabetes [13]. Direct comparison between an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and an ACE inhibitor (ONTARGET trial) did not show any significant difference in terms of preventing the progression of renal failure associated with hypertension [13].

Adverse reactions are less frequent with ARBs than ACE inhibitors (e.g., dry cough induced by the bradykinin-potentiating effect of ACE inhibitors), but ACE inhibitors are recommended as first-line therapy with/without Ca antagonists to reduce the cost of treatment [14, 15].

RAS inhibitors are the main agents for suppressing the progression of renal dysfunction associated with diabetes or hypertension. Drugs in this class dilate the efferent glomerular arterioles by suppressing angiotensin II and reduce the glomerular pressure, which in turn decreases proteinuria and prevents a decline of GFR [16]. It is important to lower the blood pressure and protect renal function by administration of RAS inhibitors at effective doses. However, these drugs tend to induce hyperkalemia or cause renal impairment, especially in patients with poor baseline renal function.

Ca antagonists are recommended for combination therapy with RAS inhibitors. These drugs are highly effective and economical, with no adverse effects on glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, or electrolytes. Ca antagonists are useful in hypertensive patients with renal dysfunction or diabetes, who are prone to develop electrolyte abnormalities [17].

In Japan, amlodipine (an L-type Ca antagonist) and benidipine (an L/T type Ca antagonist) are frequently used with the aim of also preventing vasospastic angina [17]. Our present study suggested a renoprotective effect of benidipine compared to amlodipine in diabetic CKD patients with diabetes who had failed to respond to ACE inhibitor monotherapy. This result suggests that the efficacy of Ca antagonists for hypertensive patients with CKD or diabetes may be dependent on the Ca channel subtypes targeted by these drugs [18].

Ca antagonists target voltage-dependent calcium channels, which have several subunits with differing functions (classified as L-type, T-type, or N-type) that show different patterns of distribution in the kidney [18]. In the renal microvasculature, L-type Ca channels are only expressed in the afferent arterioles and not in the efferent arterioles, while T-type and N-type Ca channels are found in both afferent and efferent arterioles and in the nerve terminals regulating these arterioles. Differences in the distribution of different types of Ca channels may have an influence on glomerular pressure [18].

Many Ca antagonists are in clinical use and may show differing effect on the Ca channel subtypes. Representative Ca antagonists like nifedipine and amlodipine only act on L-type Ca channels, while benidipine acts on T-type Ca channels in addition to L-type Ca channels [19].

During progression of renal dysfunction, glomerular hypertension causes glomerulosclerosis, leading to an increase of proteinuria. L-type Ca antagonists may increase the glomerular pressure if the systemic blood pressure is not fully controlled, because L-type Ca channels are only expressed in the afferent arterioles. On the other hand, T-type Ca channels are expressed in both afferent and efferent arterioles. It has been reported that inhibition of T-type Ca channels dilates the afferent and efferent arterioles, alleviates glomerular hypertension [14], and prevents proteinuria and deterioration of GFR.

Inhibition of T-type Ca channels may also suppress renal fibrosis, since one of the characteristic effects of L/T-type Ca antagonists is stronger suppression of aldosterone production than L-type Ca antagonists and aldosterone is involved in renal fibrosis due to its effects on the renal vasculature.

Various hypotheses have been suggested to explain the progression of diabetic nephropathy, including RAS activation [12, 20]. Hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia increase the plasma aldosterone level. In CKD patients with diabetes, enhanced local RAS activity also increases aldosterone production and leads to contraction of the afferent and efferent arterioles, resulting in chronic hypoxia and inflammation in the kidney, as well as glomerular hypertension and angiopathy with exacerbation of renal dysfunction [12, 20].

T-type Ca channels are expressed in the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal cortex, which is the site of aldosterone production, and it was reported that L/T type Ca antagonists suppress aldosterone production. L-type Ca antagonists may increase proteinuria, while T-type Ca antagonists may show a renoprotective effect in diabetic patients due to anti-inflammatory activity and prevention of renal fibrosis by suppressing aldosterone production [12, 20].

Rho kinase may have a role in the mechanism by which benidipine suppresses the progression of renal dysfunction. Diabetic rats show increased Rho activity in the adrenal gland and enhanced urinary albumin excretion, which is suppressed by administration of a Rho kinase inhibitor. Activation of Rho/Rho kinase in renal tissue induces overexpression of factors that promote fibrosis and progression of nephropathy [21]. In diabetes, the kidney is affected by chronic hypoxia and non-oxidative energy metabolism becomes predominant. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) plays a central role in metabolism under hypoxic conditions. An increase of HIF1α worsens renal impairment, while inhibition of Rho kinase facilitates degradation of HIF1α and suppresses the progression of renal dysfunction [21].

In a rat model of diabetes, glomerular expression of Rho kinase is increased and benidipine reduces Rho kinase expression similar to Rho kinase inhibitors. Diabetic rats also show increased expression of Rock 1 mRNA, with Rho kinase inhibitors and benidipine suppressing its expression. Accordingly, benidipine may suppress Rho kinase activation and progression of diabetic nephropathy [22].

In the present study, we used an ACE inhibitor as basal therapy. Strict control of blood pressure is important in patients with diabetes and addition of a Ca antagonist is useful to achieve the target blood pressure. Dose escalation of the Ca antagonist rather than the RAS inhibitor may be a treatment option for poor blood pressure control, because Ca antagonists have a renoprotective effect while RAS inhibitors can worsen renal function or cause hyperkalemia.

Benidipine blocks the T-type Ca channel, lowers the glomerular pressure, and suppresses aldosterone production, making it suitable for treatment of diabetic nephropathy. Use of benidipine should be recommended for diabetic patients, because it is expected to show a superior organ-protective effect over amlodipine (and other L-type Ca antagonists) in addition to its antihypertensive effect.

Conclusion

The effects on renal function of the Ca antagonists amlodipine and benidipine were prospectively compared in hypertensive patients with CKD when these drugs were administered concomitantly with the ACE inhibitor perindopril. The primary endpoint (eGFR) showed no change in either group. However, among the patients with diabetes, eGFR decreased significantly in the amlodipine group, but did not change in the benidipine group.

This study showed that concomitant administration of an ACE inhibitor and benidipine (a T/L type Ca antagonist) in hypertensive patients with diabetic nephropathy may suppress deterioration of renal function compared to use of an ACE inhibitor and amlodipine (an L type Ca antagonist). These results suggest a renoprotective effect of benidipine in CKD patients with diabetes.

Limitations

The CHAT-BP study was performed in patients with relatively mild hypertension and the number of subjects analyzed was not large. In addition, we did not investigate the influence of different doses of benidipine or amlodipine, which may have biased the findings.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Chikushi-JRN for recruiting patients to the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have received financial support from Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd.

| References | ▴Top |

- Bakris GL, Williams M, Dworkin L, Elliott WJ, Epstein M, Toto R, Tuttle K, et al. Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: a consensus approach. National Kidney Foundation Hypertension and Diabetes Executive Committees Working Group. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36(3):646-661.

doi pubmed - de Galan BE, Perkovic V, Ninomiya T, Pillai A, Patel A, Cass A, Neal B, et al. Lowering blood pressure reduces renal events in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(4):883-892.

doi pubmed - Nakayama M, Metoki H, Terawaki H, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Sato T, Nakayama K, et al. Kidney dysfunction as a risk factor for first symptomatic stroke events in a general Japanese population--the Ohasama study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(7):1910-1915.

doi pubmed - Irie F, Iso H, Sairenchi T, Fukasawa N, Yamagishi K, Ikehara S, Kanashiki M, et al. The relationships of proteinuria, serum creatinine, glomerular filtration rate with cardiovascular disease mortality in Japanese general population. Kidney Int. 2006;69(7):1264-1271.

doi pubmed - Bakris GL, Sarafidis PA, Weir MR, Dahlof B, Pitt B, Jamerson K, Velazquez EJ, et al. Renal outcomes with different fixed-dose combination therapies in patients with hypertension at high risk for cardiovascular events (ACCOMPLISH): a prespecified secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9721):1173-1181.

doi - Fujita T, Ando K, Nishimura H, Ideura T, Yasuda G, Isshiki M, Takahashi K, et al. Antiproteinuric effect of the calcium channel blocker cilnidipine added to renin-angiotensin inhibition in hypertensive patients with chronic renal disease. Kidney Int. 2007;72(12):1543-1549.

doi pubmed - Abe M, Okada K, Maruyama N, Matsumoto S, Maruyama T, Fujita T, Matsumoto K, et al. Benidipine reduces albuminuria and plasma aldosterone in mild-to-moderate stage chronic kidney disease with albuminuria. Hypertens Res. 2011;34(2):268-273.

doi pubmed - Ogawa S, Mori T, Nako K, Ito S. Combination therapy with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors and the calcium channel blocker azelnidipine decreases plasma inflammatory markers and urinary oxidative stress markers in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Hypertens Res. 2008;31(6):1147-1155.

doi pubmed - Patel A, Group AC, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Woodward M, Billot L, et al. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):829-840.

doi - Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, Stoyanovsky V, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1887-1898.

doi pubmed - Kimura K, et al. Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline for CKD. Japanese Society of Nephrology. 2013; xiv.

- Akizuki O, Inayoshi A, Kitayama T, Yao K, Shirakura S, Sasaki K, Kusaka H, et al. Blockade of T-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels by benidipine, a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, inhibits aldosterone production in human adrenocortical cell line NCI-H295R. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;584(2-3):424-434.

doi pubmed - Barnett AH, Bain SC, Bouter P, Karlberg B, Madsbad S, Jervell J, Mustonen J, et al. Angiotensin-receptor blockade versus converting-enzyme inhibition in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(19):1952-1961.

doi pubmed - Wu HY, Huang JW, Lin HJ, Liao WC, Peng YS, Hung KY, Wu KD, et al. Comparative effectiveness of renin-angiotensin system blockers and other antihypertensive drugs in patients with diabetes: systematic review and bayesian network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6008.

doi pubmed - Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Segal R, Martinez FA, Dickstein K, Camm AJ, Konstam MA, et al. Effect of losartan compared with captopril on mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure: randomised trial - the Losartan Heart Failure Survival Study ELITE II. Lancet. 2000;355(9215):1582-1587.

doi - Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(20):1456-1462.

doi pubmed - Mancia G, Laurent S, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Burnier M, Caulfield MJ, Cifkova R, et al. Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension Task Force document. J Hypertens. 2009;27(11):2121-2158.

doi pubmed - Hayashi K, Homma K, Wakino S, Tokuyama H, Sugano N, Saruta T, Itoh H. T-type Ca channel blockade as a determinant of kidney protection. Keio J Med. 2010;59(3):84-95.

doi pubmed - Furukawa T, Nukada T, Namiki Y, Miyashita Y, Hatsuno K, Ueno Y, Yamakawa T, et al. Five different profiles of dihydropyridines in blocking T-type Ca(2+) channel subtypes (Ca(v)3.1 (alpha(1G)), Ca(v)3.2 (alpha(1H)), and Ca(v)3.3 (alpha(1I))) expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;613(1-3):100-107.

doi pubmed - Isaka T, Ikeda K, Takada Y, Inada Y, Tojo K, Tajima N. Azelnidipine inhibits aldosterone synthesis and secretion in human adrenocortical cell line NCI-H295R. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;605(1-3):49-52.

doi pubmed - Wu G, Xu M, Xu K, Hu Y. Benidipine protects kidney through inhibiting ROCK1 activity and reducing the epithelium-mesenchymal transdifferentiation in type 1 diabetic rats. J Diabetes Res. 2013;2013:174526.

doi pubmed - Sugano N, Wakino S, Kanda T, Tatematsu S, Homma K, Yoshioka K, Hasegawa K, et al. T-type calcium channel blockade as a therapeutic strategy against renal injury in rats with subtotal nephrectomy. Kidney Int. 2008;73(7):826-834.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.