| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.jocmr.org |

Original Article

Volume 13, Number 5, May 2021, pages 309-316

Influence of Luseogliflozin on Vaginal Bacterial and Fungal Populations in Japanese Patients With Type 2 Diabetes

Masataka Kusunokia, e, Kazuhiko Tsutsumib, Naomi Wakazonoa, Fumiya Hisanoc, Tetsuro Miyatad

aDepartment of Diabetes, Motor Function and Metabolism, Research Center of Health, Physical Fitness and Sports, Nagoya University, E5-2 (130), Furou-cho, Chigusa-ku, Nagoya City, Aichi 464-0814, Japan

bOkinaka Memorial Institute for Medical Research, 2-2-2 Tranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8470, Japan

cGraduate School of Medicine, Department of Integrated Health Sciences, Nagoya University, 1-1-20 Daiko-Minami, Higashi-ku, Nagoya City, Aichi 461-8673, Japan

dOffice of Medical Education, School of Medicine, International University of Health and Welfare, 4-3, Kozunomori, Narita-shi, Chiba 286-8686, Japan

eCorresponding Author: Masataka Kusunoki, Department of Diabetes, Motor Function and Metabolism, Research Center of Health, Physical Fitness and Sports, Nagoya University, E5-2 (130), Furou-cho, Chigusa-ku, Nagoya City, Aichi 464-0814, Japan

Manuscript submitted April 13, 2021, accepted April 27, 2021, published online May 25, 2021

Short title: Influence of Luseogliflozin on Vaginal Flora

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr4504

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Selective sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, known to lower the blood glucose levels by promoting the urinary glucose excretion, can predispose to genitourinary infections. This prospective study investigated the influence of selective sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors luseogliflozin on the vaginal flora of the pre- and postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods: Twelve premenopausal and 24 postmenopausal female Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus took luseogliflozin 2.5 mg once daily for 6 months. The intravaginal fungal and bacterial populations, together with the body weight and serum parameters of diabetes mellitus and lipid metabolism were measured before and after the treatment.

Results: After luseogliflozin treatment, the body weight, body mass index and hemoglobin A1c decreased, and the serum levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol increased significantly. Luseogliflozin treatment revealed to increase vaginal colony concentrations of Enterococcus faecalis (P = 0.0077) and E. coli (P = 0.0201) in premenopausal patients, and Enterococcus faecalis (P = 0.0051) and Candida albicans (P = 0.0355) in postmenopausal patients. In both pre- and postmenopausal patients, colony concentrations of Staphylococcus spp. had decreased (P = 0.0261 and P = 0.0161).

Conclusions: Treatment with selective sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors luseogliflozin was associated with changes of the vaginal flora. These findings provide basic data on the increased susceptibility to genital infections during luseogliflozin treatment.

Keywords: Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor; Genital infections; Vaginal flora; Menopause; Type 2 diabetes mellitus

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) is a carrier protein expressed in the proximal tubules of the kidneys, that is responsible for reabsorption of about 90% of the glucose filtered through the glomeruli [1, 2]. SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) are known to exert a blood-glucose-lowering effect by increasing the urinary excretion of blood glucose [3]. In addition to exerting a blood-glucose-lowering effect, SGLT2is have also been reported to have the effects of reducing the body weight, lowering the blood pressure and improving lipid and uric acid metabolism [4]. It has been reported that through these multifaceted activities, SGLT2is can significantly suppress cardiovascular death and heart failure in patients at elevated cardiovascular risk [5].

While SGLT2is have these clinical advantages over other hypoglycemic agents, they can also have unique adverse effects based on the mechanism by which they lower the blood glucose level. SGLT2is act by increasing the urinary glucose levels and increasing the risk of genitourinary infections. While there are reports dealing with the incidence of such infections [6, 7], reports on the influence of SGLT2i treatment on the causative bacteria or fungi for genitourinary infections remain scarce.

Genitourinary infections arising as a result of elevated urinary glucose levels are seen in both males and females; however, they pose a clinical problem more frequently in females than in males. The incidences of genital infections in females have been reported to differ between premenopausal and postmenopausal women [8]. Bearing these in mind, we undertook the present study to evaluate the influence of treatment with luseogliflozin, an SGLT2i, on the vaginal fungal and bacterial flora in diabetic women divided into premenopausal and the postmenopausal groups. Recently, SGLT2is have also been approved for the treatment of type 1 diabetes and cardiac failure in Japan. Therefore, further studies to investigate the side effects of SGLT2is are indispensable.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution for studies in human subjects as well as with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the Medical Corporation Odakai Ethics Committee (IRB approval number 2014-03). Patients who participated in the study were provided an explanation about the purpose of the study by the physicians in charge, and gave informed consent. This prospective clinical study is officially registered as an open-label study (ID: UMIN000025334).

Subjects

Female patients who were diagnosed to have diabetes with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values between 6.5% and 9% were selected for this study, and patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 45 were excluded from the study. As a result, the study was conducted in 36 female Japanese outpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, consisting of 12 premenopausal women (40 ± 6 years old) and 24 postmenopausal women (62 ± 6 years old). These patients were also taking antidiabetic drugs other than SGLT2i, lipid-lowering drugs (statin, fibrate, EPA, or ion exchange resin) and/or anti-hypertensive drugs (calcium antagonist, or ACE inhibitor). They did not receive diuretics. Each patient took the SGLT2i luseogliflozin at the dose of 2.5 mg once daily (before or after breakfast) for 6 months. None of the patients had any clinical symptoms of genital infection before the start of administration of luseogliflozin.

Body weight and serum lipid measurement

Body weight and height were measured immediately before and at the end of 6 months of luseogliflozin treatment and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Blood samples were obtained before and after the treatment. Sera were separated from the blood samples for measurement of the serum biochemical parameters. Each serum sample was stored frozen at -80 °C until the measurements. Measurements of the serum HbA1c and total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and triglyceride (TG) levels were assigned to Handa Medical Association Health Center (Aichi, Japan). Serum lipids were measured with an auto-analyzer (JCA-BM8000 series, JAOL, Tokyo, Japan). HbA1c measurement was conducted by HPLC (HLC-723GX, Tosoh Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Determination of intravaginal fungal and bacterial populations

Immediately before and after 6 months of luseogliflozin treatment, the vulva of each patient was washed with water and the vaginal secretions were collected with a sterile cotton applicator. The secretions collected were incubated in the following four kinds of media for identification and quantification of the fungi and bacteria; the culture media used were blood agar medium, chocolate agar medium, bromothymol blue agar medium and CHROM agar medium (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Tokyo, Japan). Using these media suitable for individual fungi or bacteria, incubations were carried out by methods reported elsewhere [9]. Gram staining was performed to identify the types of bacteria. Then, the colony counts of each fungus and bacterium were evaluated based on the colony concentration score rated macroscopically on a four-grade scale, as follows: 1+ (colonies occupying 1/4 of the total area of the bacterial culture dish); 2+ (colonies occupying 1/2 of the total area of the culture dish); 3+ (colonies occupying 3/4 of the total area of the culture dish); 4+ (colonies grown to confluence in the dish). In this study, bacteria that have the potential to cause infections were analyzed.

The effects of luseogliflozin treatment on the intravaginal fungal and bacterial populations were evaluated separately in the premenopausal group (n = 12) and the postmenopausal group (n = 24) of women.

Statistical analysis

The measured data (body weight, BMI, HbA1c and serum lipid parameters) were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The colony concentration score of each vaginal fungus or bacterium per patient was expressed in numerical values, i.e., score 1+ as 1, score 2+ as 2, score 3+ as 3, and score 4+ as 4, and the sum of these values of the patients was used as a quantitative evaluation index of each fungal or bacterial proliferation. The data before and 6 months after the administration of luseogliflozin were compared using the paired t-test and the statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05.

| Results | ▴Top |

Effects of luseogliflozin on the body weight, HbA1c and serum lipid parameters

The body weight, BMI and HbA1c after 6 months of luseogliflozin treatment were significantly lower than the values recorded before the start of treatment. Analysis of the serum lipid profile revealed no influence of luseogliflozin treatment on the serum levels of total cholesterol, LDL-C or TG, while the serum HDL-C rose significantly after the treatment (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Effects of Luseogliflozin on Body Weight, BMI, HbA1c and Serum Lipid Parameters (N= 36) |

Influence of luseogliflozin treatment on the vaginal fungal and bacterial populations

In two women of the premenopausal group who were positive for Candida glabrata before treatment, the luseogliflozin treatment was suspended for 2 - 3 weeks to enable eradication of the fungus, with the treatment later resumed at the request of these patients and continued until the end of the clinical study. There were no clinical adverse effects in any of these cases. During the study periods, only two premenopausal patients with positive detection of Candida albicans complained of vulval itching, one of clinical symptoms of genital infection.

Influence of luseogliflozin treatment on vaginal fungal populations

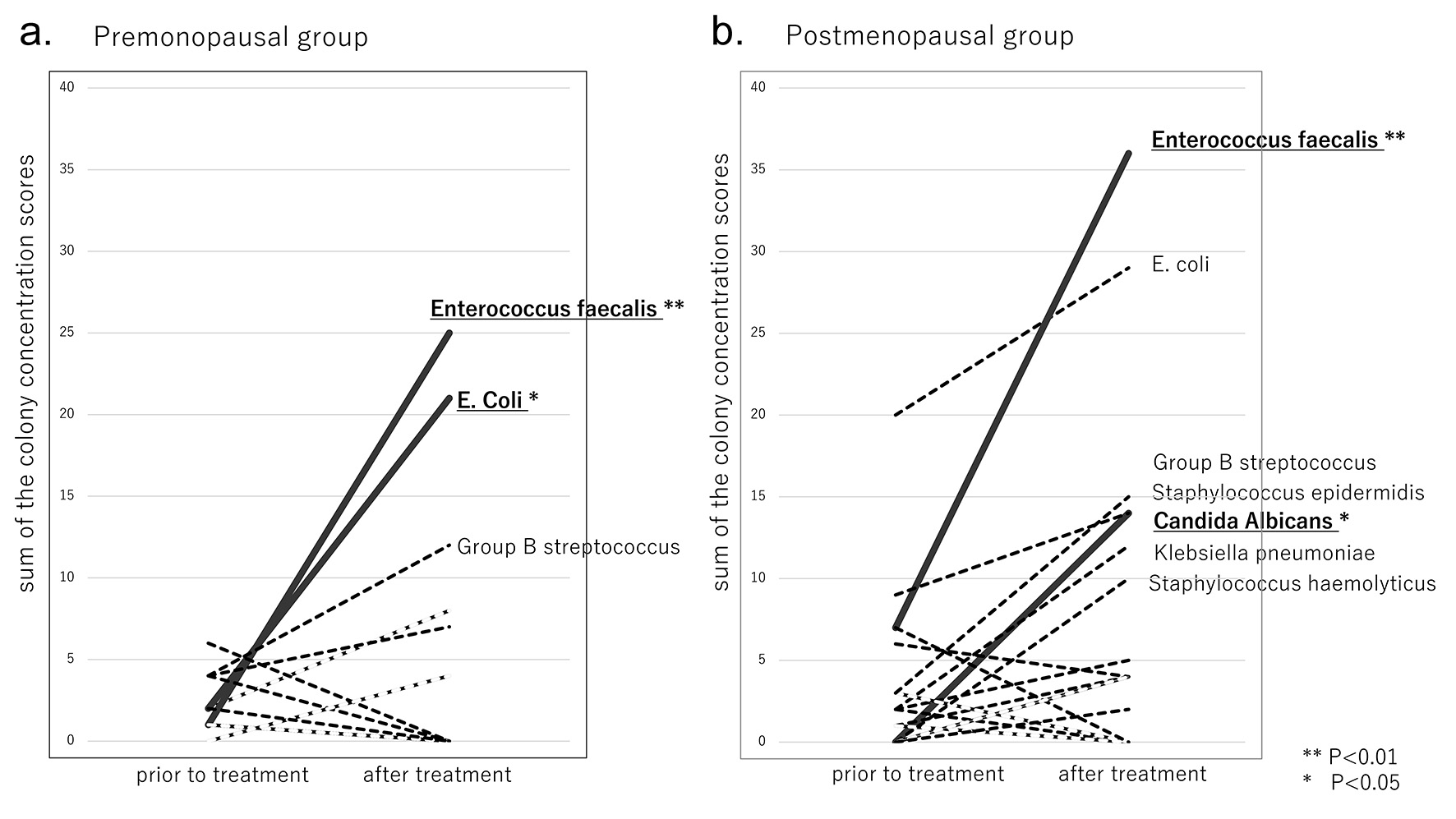

Three fungal species (Candia albicans, Candia glabrata and Candida krusei) were identified by culture (Table 2). Statistical analysis of the differences in the sum of the colony concentration scores showed that in the premenopausal group, the score for none of the three species of fungi was significantly affected by luseogliflozin treatment. On the contrary, Candida albicans was the only fungus that showed significant proliferation after luseogliflozin treatment (P = 0.0355), while no fungi could be detected before the start of administration of luseogliflozin, in the postmenopausal group (Fig. 1b).

Click to view | Table 2. Effects of Luseogliflozin on the Intravaginal Fungal Populations |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Changes in the sum of the concentration scores prior to and after luseogliflozin treatment. (a) Premenopausal group. (b) Postmenopausal group. |

Influence of luseogliflozin treatment on vaginal gram-negative bacterial populations

Ten gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Morganella morganii, Citrobacter farmer, Gardnerella vaginalis, Enterobacter cloacae, Enterobacter aerogenes, Citrobacter freundii, Acinetobacter baumannii and Proteus vulgaris) were identified by culture (Table 3). Before treatment, the sums of colony concentration scores were < 10 for each species, except E. coli in the postmenopausal group. After treatment, the scores increased to ≥ 10 for E. coli in the premenopausal group (Fig. 1a), and for two bacterial species (E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae) in the postmenopausal group (Fig. 1b). Statistical analysis of the differences in the scores showed that in the premenopausal group, E. coli was the only species that showed significantly increased proliferation after luseogliflozin treatment (P = 0.0201); no such increase was observed in the postmenopausal group. Although a large increase of the score for E. coli was detected after luseogliflozin treatment in the postmenopausal group, the increase was not significant, since many colonies of E. coli were already observed before the start of the treatment.

Click to view | Table 3. Effects of Luseogliflozin on the Intravaginal Gram-Negative Bacterial Populations |

Influence of luseogliflozin treatment on vaginal gram-positive bacterial populations

Seventeen gram-positive bacteria (Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus gallinarum, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Corynebacterium spp., Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus cohnii, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Staphylococcus spp., Staphylococcus simulans, Staphylococcus lentus, α-Staphylococcus, Staphylococcus sciuri, Staphylococcus lugdunensis, Streptococcus anginosis, Staphylococcus capitis and group B streptococcus) were identified by culture (Table 4). Before treatment, sums of the colony concentration scores were < 10 for each species. After treatment, the scores increased to ≥ 10 for two bacterial species (Enterococcus faecalis and group B streptococcus) in the premenopausal group (Fig. 1a), and for one fungal and four bacterial species (Candida albicans, Enterococcus faecalis, group B streptococcus, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus hemolyticus) in the postmenopausal group (Fig. 1b). In both the pre- and postmenopausal groups, statistical analysis of the differences in the colony concentration scores showed that only the score for Enterococcus faecalis increased significantly (P = 0.0077 and P = 0.0051), and that for Staphylococcus spp. decreased significantly (P = 0.0261 and P = 0.0161) after luseogliflozin treatment.

Click to view | Table 4. Effects of Luseogliflozin on the Intravaginal Gram-Positive Bacterial Populations |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

To date, few reports have been published concerning the influence of luseogliflozin treatment on the changes of vaginal fungal and bacterial populations. The present study was designed to evaluate the influence of treatment with the SGLT2i luseogliflozin for 6 months on the changes of vaginal flora, which could become the risk of genitourinary infection, in 36 Japanese women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Our results indicated that luseogliflozin treatment was associated with statistically significant increases in the vaginal colony counts of Enterococcus faecalis and E. coli in premenopausal patients, and that of vaginal Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans in postmenopausal patients. In both the pre- and postmenopausal group, colony count of Staphylococcus spp. decreased significantly after luseogliflozin treatment. The present study results were consistent with the effects of luseogliflozin treatment reported by Kusunoki et al [10], with reduction of the serum HbA1c, body weight, BMI, and no changes in the serum levels of total cholesterol, LDL-C or TG, but elevation of the serum HDL-C following the luseogliflozin treatment; these results indicate that luseogliflozin treatment was effective in our series.

The incidences of genital infections have been reported to differ between premenopausal women and postmenopausal women [8]. The vaginal microflora is often influenced by the ovarian function, especially the amount of estrogen and the vaginal pH. The types and numbers of bacteria detected are significantly reduced in postmenopausal women as compared to premenopausal women. The vaginal pH is lower in premenopausal women, with Lactobacillus spp. accounting for a large part of the vaginal flora, but after menopause, the vaginal pH increases and the Lactobacillus population decreases, and instead, non-specific bacteria account for the majority of the flora. As the presence of Lactobacillus spp. plays an important role in the defense against vaginal infections, postmenopausal women have increased risk of vaginal infections [8]. In addition, it has also been reported that the incidence of genital infections is higher in premenopausal women with high sexual activity and lower in postmenopausal women with low sexual activity [11].

Lactobacillus spp., Peptostreptococcus spp., Bacteroides spp., coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, E. coli and Diphtheroides are of detected bacterial species in the vagina in both pre- and postmenopausal women. Among these, E. coli, Bacteroides spp., and, even though detected at lower frequencies, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Candida spp., are pathogenic bacteria [8].

In this study, the relatively frequently detected intravaginal fungi and bacteria before the start of luseogliflozin treatment were Staphylococcus spp. (42%), Staphylococcus epidermidis (33%), E. coli (17%), Candida albicans (17%) and Candida glabrata (17%) in the premenopausal women, and E. coli (63%), Staphylococcus epidermidis (38%) and Enterococcus faecalis (29%) in the postmenopausal women. No fungi were detected in the postmenopausal group. Although the types and numbers of bacteria have been reported to decrease after menopause, in our series, the types and numbers of bacteria did not change significantly even after menopause.

On the other hand, administration of luseogliflozin changed the vaginal fungal and bacterial flora; treatment with luseogliflozin caused significant increases in the colony counts of Enterococcus faecalis and E. coli spp. in premenopausal women, significant increases in the populations of Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans spp. in postmenopausal women, and significant decreases in the populations of Staphylococcus spp. irrespective of the menopausal status of the women. In addition, postmenopausal women receiving luseogliflozin treatment showed an increase in E. coli spp., although the increase was not significant, since many E. coli spp. were already observed before the drug treatment. SGLT2i is a very promising drug in the treatment of diabetes. However, as a result of its administration, the growth of certain vaginal fungal and bacterial flora was clarified. The increase of specific fungal and bacterial species can lead to an unfavorable increase in urinary or genital infections caused by those species.

Enterococcus faecalis is a normal inhabitant of the gut and is found in most healthy people. However, in rare cases, it causes urinary tract infection and sepsis, and it is also a feared causative organism of endocarditis. Emergence of antibiotic resistant strains of this bacterium is a problem in the medical setting. In patients treated with luseogliflozin, a remarkable increase in the colony counts of this bacterial species was observed in the vaginal flora in both the pre- and postmenopausal women. This finding suggests that Enterococcus faecalis might be one of the most common causes of genital infections in patients receiving luseogliflozin treatment.

E. coli is the most abundant bacterium in the human large intestine. Pathogenic strains cause diarrhea, and all strains, even those that are not ordinarily pathogenic, can cause infections if they invade sterile sites, and urinary tract infections are the most common infections caused by E. coli. After luseogliflozin treatment, clear increases in both the percentage of patients with E. coli and the number of bacterial colonies of E. coli in each patient were observed in the premenopausal women. On the other hand, in the postmenopausal patients, although a marked increase in the number of E. coli bacterial colonies was observed in specific patients, the percentage of patients with E. coli decreased. Considering the pathogenicity of E. coli, close attention should be paid to the risk of infection caused by this bacterial species in patients receiving luseogliflozin treatment.

Candida albicans is the most common cause of vaginitis. Although luseogliflozin treatment induced changes in many vaginal fungal and bacterial populations, vaginal candidiasis was the only manifest infection that caused clinical symptoms necessitating treatment in two premenopausal patients. Therefore, provision of appropriate guidance to prevent vaginal candidiasis, which is a typical opportunistic infection, is indispensable for patients receiving luseogliflozin treatment.

Bacterial vaginitis, in particular, tends to occur more often in postmenopausal patients, as a result of the reduction in protection afforded by Lactobacillus spp.[8]. Although the increases were not significant, it is noteworthy that moderate increases in the populations of several bacterial species were observed in postmenopausal women treated with luseogliflozin, which could predispose to genital infections. This suggests the necessity for special caution to be exercised against the risk of genital infections in postmenopausal patients, as compared to premenopausal patients, receiving luseogliflozin treatment. In postmenopausal women, on sick days, when the body’s resistance to infections is reduced, it might be necessary to consider suspension of SGLT2i treatment, from the point of view of reducing the risk of genital infections caused by opportunistic microorganisms.

There were limitations of this study. The effect of luseogliflozin treatment on anerobic pathogenic bacterial species, such as Bacteroides, still remains unclear, because no anerobic cultures were performed. Since the number of patients examined was small and the numbers of premenopausal and postmenopausal patients were not equal, a simple comparison between the two groups without any control group may not be reasonable. The aim of this study was to alert physicians to the possibility of genitourinary infections occurring as an adverse effect of treatment with the SGLT2i luseogliflozin, as a result of changes in the vaginal fungal and bacterial flora. The effects of the changes in the vaginal flora on clinical disease development have not yet been clarified. In this study, only luseogliflozin was selected as an SGLT2i. But we think our observed phenomena are not specific to luseogliflozin, but common to all SGLT2is. Every SGLT2is excrete the excessive circulating glucose into the urine, and elevated glucose level in the urine can be one of the major causes of urinary or genital infection by affecting the vaginal flora in female.

Conclusions

Treatment with the SGLT2i luseogliflozin was associated with changes in the vaginal fungal and bacterial flora, with increase in the populations of specific species in female patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. These findings provide basic data on the increased susceptibility to genital infections as an adverse reaction to luseogliflozin treatment.

Acknowledgments

There is no specific acknowledgment that warrants mention.

Financial Disclosure

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial conflict of interest to report.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained.

Author Contributions

MK has designed and performed the study. MK, KT and TM have drafted the manuscript and did critical editing. NW and FH have assisted and supported in data collection and subsequent analysis with statistics.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding the availability of the supporting data from this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

SGLT2: sodium-glucose cotransporter 2; SGLT2i: sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor; BMI: body mass index; HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG: triglyceride

| References | ▴Top |

- Wright EM. Glucose transport families SLC5 and SLC50. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34(2-3):183-196.

doi pubmed - Wright EM, Loo DD, Hirayama BA. Biology of human sodium glucose transporters. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(2):733-794.

doi pubmed - DeFronzo RA, Davidson JA, Del Prato S. The role of the kidneys in glucose homeostasis: a new path towards normalizing glycaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(1):5-14.

doi pubmed - Seino Y, Sasaki T, Fukatsu A, Ubukata M, Sakai S, Samukawa Y. Efficacy and safety of luseogliflozin as monotherapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(7):1245-1255.

doi pubmed - Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-2128.

doi pubmed - Kushner P. Benefits/risks of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor canagliflozin in women for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. Womens Health (Lond). 2016;12(3):379-388.

doi pubmed - Roden M, Merker L, Christiansen AV, Roux F, Salsali A, Kim G, Stella P, et al. Safety, tolerability and effects on cardiometabolic risk factors of empagliflozin monotherapy in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes: a double-blind extension of Phase III randomized controlled trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14(12):141-154.

doi pubmed - Laskshmi K, Chitralekha S, Illamani V, Menezes GA. Prevalence of bacterial vaginal infections in pre- and postmenopausal women. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2012;3(4):B949-B956.

- Jorgensen JH, Ferraro MJ. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing: a review of general principles and contemporary practices. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(11):1749-1755.

doi pubmed - Kusunoki M, Natsume Y, Sato D, Tsutsui H, Miyata T, Tsutsumi K, Suga T, et al. Luseogliflozin, A sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, alleviates hepatic impairment in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Drug Res (Stuttg). 2016;66(11):603-606.

doi pubmed - Hooton TM. Recurrent urinary tract infection in women. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17(4):259-268.

doi

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.