| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Original Article

Volume 12, Number 5, May 2020, pages 307-314

Non-Invasive Isthmocele Treatment: A New Therapeutic Option During Assisted Reproductive Technology Cycles?

Ali Sami Gurbuza, b, d, Funda Godec, Necati Ozcimena

aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, KTO Karatay University Medical Faculty, Konya, Turkey

bNovafertil IVF Center, Konya, Turkey

cDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Bahcesehir University Medical Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey

dCorresponding Author: Ali Sami Gurbuz, Novafertil IVF Center, Yeni Meram Yolu No. 75, Meram, Konya, Turkey

Manuscript submitted March 18, 2020, accepted April 17, 2020

Short title: Non-Invasive Isthmocele Treatment

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr4140

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: The objective of the study was to evaluate a new medical treatment strategy for infertile patients with isthmocele.

Methods: This was a retrospective evaluation of the records of infertile patients with symptomatic isthmocele who received non-invasive isthmocele treatment (NIIT) before in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment cycles. Isthmocele volumes were measured before and after NIIT. The IVF results and isthmocele-related complaints were also analyzed. The patients were treated with a depot gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist for 3 months before frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles.

Results: The mean isthmocele volume was 471.06 ± 182.81 mm3 (range: 289.43 - 765.4 mm3) in fresh cycles, but was reduced to 47.94 ± 29.48 mm3 (range: 18.70 - 105.6 mm3) in frozen-thawed cycles (P < 0.05). Intrauterine fluid was observed in two patients during fresh cycles, but was absent after NIIT during frozen-thawed cycles. There was no brown bloody discharge on the tip of the embryo transfer catheter in any case after NIIT. Two patients became pregnant and underwent term cesarean delivery (25%).

Conclusions: NIIT can serve as an alternative pretreatment option for patients with isthmocele during IVF cycles.

Keywords: GnRH analogue; Isthmocele; Infertility; Non-invasive treatment

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cesarean section delivery rates have increased worldwide over the last two decades, reaching 53% in Turkey [1]. Cesarean is a major obstetric operation that can result in serious complications and morbidity. One such complication is cesarean scar defect, also known as isthmocele or niche [2, 3]. Isthmocele is a pouch defect located on the anterior wall of the uterine isthmus. Transvaginal ultrasonography and saline infusion sonography are highly sensitive methods for detecting myometrial defects, and can be applied in an office setting [4, 5]. The prevalence of isthmocele was reported as 24-70% on transvaginal ultrasound [6].

The exact pathophysiological mechanism underlying isthmocele is not known, but the most likely causes are surgical, i.e. uterine incision and closure. Insufficient incision into cervical tissue, incomplete closure of the uterine wall and use of locking sutures have been suggested as risk factors for isthmocele [7]. Double-layer closure was reported to decrease the incidence of isthmocele in previous reports [7-9]. Furthermore, certain patient-related factors may increase adhesion formation or impair wound-healing, particularly in women with a retroverted uterus [10].

Isthmocele was first noted in hysterectomy specimens in 1995 by Morris, who coined the term “cesarean scar syndrome” for cases of postmenstrual bleeding, secondary infertility and pelvic pain [11, 12]. The pathological findings of isthmocele, as confirmed in cesarean scar defect hysterectomy specimens, are inflammation, endometrial glands, fibrosis, necrosis, adenomyosis and endometriosis [11]. Chronic pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea can occur along with endometriosis [13]. The estimated risk of subsequent infertility in isthmocele cases was reported at 4-19% [14, 15]. However, the extent of the relationship between secondary infertility and isthmocele remains open to question. Both uterine and cervical factors have been implicated in infertility. Accumulation of menstrual blood in the pouch may reduce cervical mucus quality and obstruct sperm passage; it can also result in retrograde flow through the uterus, where this retained blood may be related to infection even in cases of chronic endometritis. Thus, chronic endometritis can result in implantation failure of embryos [15-19].

The treatment options for isthmocele include laparoscopic, hysteroscopic and vaginal surgery. Most of the symptoms, such as postmenstrual spotting and pelvic pain, were significantly decreased after surgical treatment in previous reports. Hysteroscopic repair of the isthmocele is the most common approach for treating infertile patients, but no previous studies have compared the available treatment options for secondary infertility [13, 16, 20-22].

Notably, there is no approved medical treatment for patients with secondary infertility. As mentioned above, endometriosis is among the pathological findings in isthmocele; therefore, we thought that medical treatment of this symptom may be beneficial in patients with secondary infertility. The treatment options for infertile patients with endometriosis include intrauterine insemination and in vitro fertilization (IVF), depending on the severity of the disease. When IVF is chosen, prolonged (≥ 3 months; ultralong protocol) pituitary downregulation using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRh) agonist is recommended [23]. In a previous meta-analysis, an ultralong protocol was reported to increase the pregnancy rate four-fold among patients with endometriosis [24]. GnRh agonists are preferred for treating the symptoms of endometriosis because they suppress menstruation. Therefore, non-invasive isthmocele treatment (NIIT) may be an alternative to surgery for isthmocele before IVF. In the present study, we evaluated the NIIT outcomes of eight patients with isthmocele during IVF cycles and reviewed the relevant literature.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

We performed a retrospective review of the medical records of eight infertile patients who received NIIT before IVF cycles. All of the included patients presented to Novafertil IVF Center between September 2016 and September 2018. This study was a retrospective case series, and Novafertil IVF Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained before the beginning of study. This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution on human subjects as well as with the Helsinki Declaration.

Patients

The clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Six patients had undergone one previous cesarean section, whereas two others had undergone two cesarean sections. Case 4 underwent a vaginal delivery before cesarean section. All of the patients exhibited postmenstrual bleeding and secondary infertility. The etiological factors of infertility were as follows: tubal factor infertility in four patients (two of whom underwent tubal ligation); male factor infertility in three patients; and unexplained infertility in one patient. The mean age of the patients was 35 years (range: 29 - 39 years). Seven patients had a history of previous IVF treatment failure after cesarean section.

Click to view | Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Patients |

Ovulation induction via NIIT

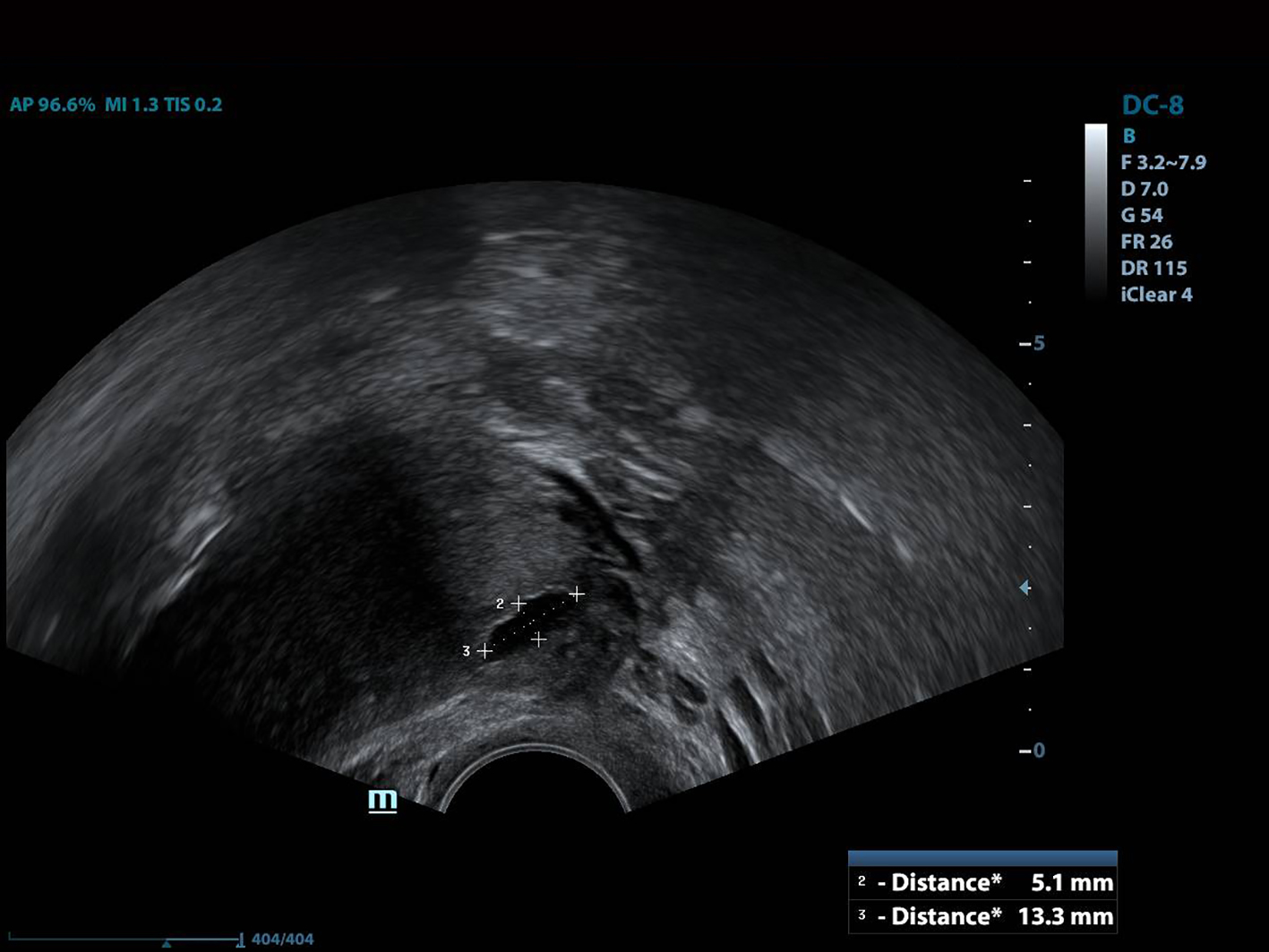

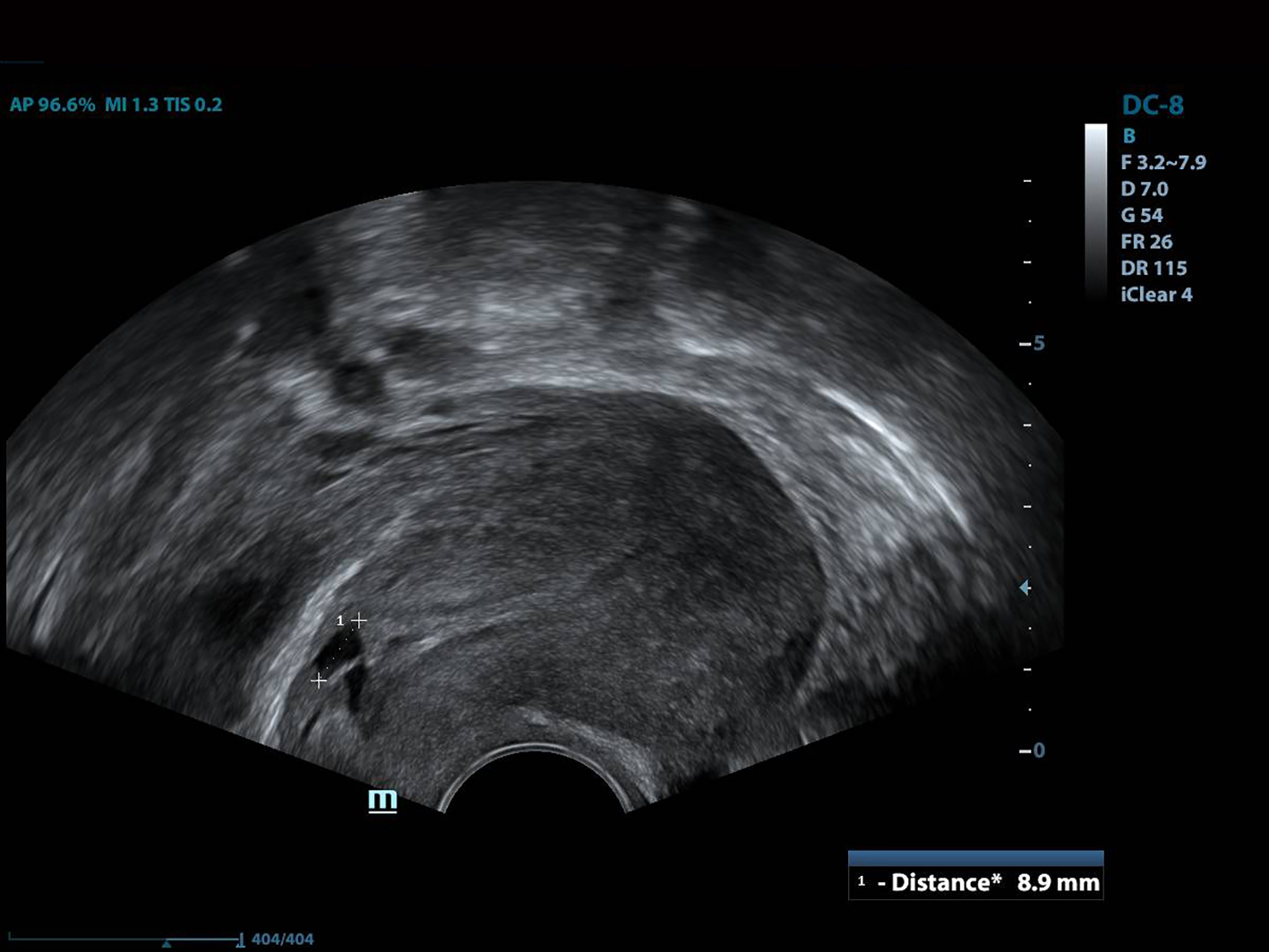

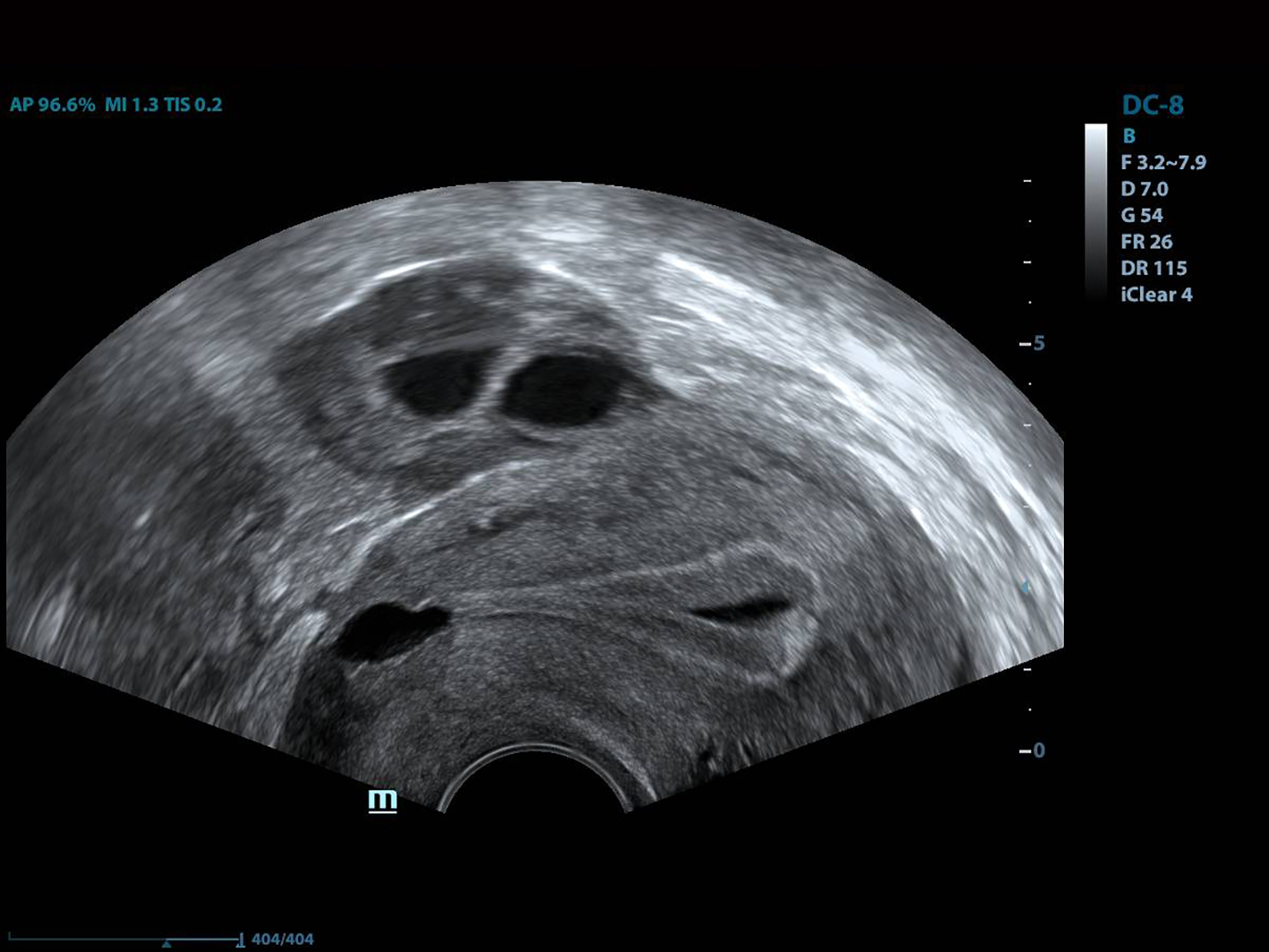

All of the patients underwent GnRh antagonist treatment. Ovarian stimulation with recombinant follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) was started on day 2 of menstruation. When the leading follicle exceeded 14 mm in length, a gonadotropin antagonist (Cetrotide, 0.25 mg; Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) was started and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; Ovitrelle, 250 µg; Merck) was administered when there were at least two follicles > 18 mm in length. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided follicular aspiration was performed at 36 h after hCG injection. All women underwent transvaginal ultrasonography on the trigger day. The height, depth and width of the isthmocele were measured, and the volume was calculated (Figs. 1, 2). Residual myometrial thickness was also measured on the same day. Ultrasonographic images were taken of each patient. The embryos were frozen at 3 days after the intracytoplasmic sperm injection procedure. The depot GnRH agonist leuprolide acetate (3.75 mg; Lucrin Depot, Abbott, Istanbul, Turkey) was administered to all patients on day 1 following three consecutive months. Oral estrogen (Estrofem, three times daily) treatment was started at 20 days after the last GnRH analog dose. When the endometrium became suitable for embryo transfer, the isthmocele volume was remeasured and new ultrasonography images were acquired (Fig. 3). Embryo transfer was performed at 3 days after progesterone administration. A pregnancy test was performed on day 12 after embryo transfer. The pregnant patients were followed up and infants were delivered by cesarean section. All patients were managed by the same clinician.

Click for large image | Figure 1. The height and width of the isthmocele measurement. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. The depth of the isthmocele measurement. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. The view of the isthmocele before embryo transfer. |

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 20.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For the statistical methods, for paired comparison between groups Wilcoxon signed rank test was used. A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

| Results | ▴Top |

The IVF results of the patients are summarized in Table 2. The mean myometrial thickness was below 3 mm (range: 0.8 - 2.6 mm) in all patients. The mean isthmocele volume was 471.06 ± 182.81 mm3 (range: 289.43 - 765.4 mm3) in fresh cycles, but was reduced to 47.94 ± 29.48 mm3 (range: 18.70 - 105.6 mm3) in frozen-thawed cycles (P < 0.05). These data are shown in Table 2 and residual myometrial thickness data are shown in Table 1. Intrauterine fluid was observed in two patients on fresh cycles, but not in patients on frozen-thawed cycles, after NIIT. There was no brown bloody discharge on the tip of the embryo transfer catheter in any case after NIIT. All patients had a retroverted uterus.

Click to view | Table 2. In Vitro Fertilization Treatment Results and Isthmocele Volumes of the Patients |

Two patients became pregnant and underwent term cesarean delivery (cases 5 and 7). Six patients had negative results for B-human chorionic gonadotropin (bhCG). Case 5 had a negative result on a previous IVF cycle but became pregnant after NIIT. Her isthmocele was excised and sutured primarily during cesarean section; the scar tissue was 7.3 mm in size at 4 months postpartum. Pregnancy was achieved in case 7 and her isthmocele was also excised and repaired during cesarean section; the scar tissue was 9.4 mm in size at 4 months postpartum. Neither of these patients exhibited postmenstrual bleeding after the operation.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Isthmocele is a common complication after cesarean section. With the increasing use of cesarean section worldwide over the last two decades, awareness of this complication and related issues has become more important. Currently, surgical treatment of symptomatic isthmocele is preferred over expectant or medical management. Hysteroscopic, laparoscopic and vaginal approaches represent the current surgical options, but there is no evidence regarding which method is most effective.

Hysteroscopy is currently the first choice treatment because it is minimally invasive and yields good therapeutic results [16]. Hysteroscopic isthmoplasty is performed by resection of the cephalad and caudal margins and ablation of the isthmocele cavity [16]. This operation has the advantage of a relatively short duration, but uterine perforation and injury to adjacent organs are potential complications. Moreover, the risks of cervical insufficiency and uterine rupture in future pregnancies are not known. Therefore, if the myometrial thickness is less than 3 mm over the isthmocele, a vaginal, laparoscopic, or robotic-assisted approach is recommended to strengthen the anterior wall [25].

Laparoscopic surgery has been considered a good option to obtain an optimal view during dissection of the vesico-vaginal space, and for avoiding bladder injuries [13]. However, the long duration of the operation and necessity for surgical experience are disadvantages of this surgery, and the treatment outcomes reported in the literature are equivocal. According to Drouin et al, recovery of residual myometrium was unremarkable and infertility was not resolved after laparoscopic repair of the isthmocele [26]. Elsewhere, it was reported that symptoms were not resolved in 18.2-36.4% of patients after laparoscopic surgery [27]. Vaginal surgery is another option, involving excision of scar tissue and primary suturation via the vaginal route. The lower cost and shorter duration of this operation constitute its main advantages, but the narrow surgical space can be problematic for inexperienced clinicians [28-30]. However, consensus is lacking because no studies have compared the different surgical approaches for patients with isthmocele.

All of the aforementioned treatments are surgical in nature, and thus carry an inherent risk of complications. Accordingly, medical treatment may be a safer option to address the symptoms of isthmocele, which are mostly related to menstruation such that suppression of bleeding may be beneficial. Oral contraceptives, progesterone and GnRH agonists are rational options for suppression of bleeding and symptom relief. Interestingly, only one study in the literature compared hormonal treatment with hysteroscopic surgery. In that study, one group of patients with menstrual complaints received ethinyl estradiol-gestodene and a second group underwent hysteroscopic isthmocele repair. The primary outcome was postmenstrual abnormal uterine bleeding (PAUB). Although PAUB and pelvic pain were resolved in both groups, the hysteroscopy group experienced fewer days of menstrual bleeding [12].

Histopathologic evaluation of cesarean scar defect revealed that, in some cases, endometriosis was present on the scar defect [19, 31]. The blood in the isthmocele may originate from menstrual blood in the uterus or endometriosis in the scar region [25]. Such blood, as well as mucus, was shown to be related to sperm penetration problems and implantation defects [32, 33]. An ultralong protocol was reportedly associated with higher pregnancy rates in patients with endometriosis [20]. Furthermore, long-term downregulation with GnRH agonist treatment was related to clinical improvement of pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia. Taketani et al reported that GnRH agonist treatment reduced peritoneal fluid concentrations of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor in patients with endometriosis to levels below those in untreated controls [34]. A beneficial effect of GnRH agonist therapy on natural killer cell activity was also reported by Garzetti et al [35]. Histologic evaluation revealed chronic inflammatory infiltration in the majority of isthmocele patients [12]. This hemorrhagic fluid pools in the uterine cavity and thus impairs implantation of the embryo, similar to hydrosalpingeal fluid (which was shown to be related to implantation defects in IVF cycles) [36]. As with an ultralong protocol, GnRH agonist downregulation therapy for at least 3 months attenuates blood accumulation in the isthmocele and endometriosis in the scar tissue. Thus, if reproductive treatment is planned in an isthmocele patient, NIIT could be a useful option. Another important phenomenon is the brown bloody discharge observed on the tip of the embryo transfer catheter after embryo transfer in most isthmocele patients. The origin of this discharge is the liquid inside the uterine cavity (Fig. 4). We noted no such discharge in any case treated with NIIT in this study. Also, there was neither postmenstrual spotting nor blood accumulation in the isthmocele in our patients after treatment. Frozen-thawed embryo transfer may be a better option than fresh embryo transfer in isthmocele cases. Estrogen levels in frozen embryo transfer cycles are lower than those in fresh cycles, which in turn lead to lower levels of secretion and fluid accumulation in the uterine cavity.

Click for large image | Figure 4. The view of the intrauterine fluid. |

Accumulated blood and fluid may be related to infection and chronic endometritis in isthmocele cases. This inflammatory process can resemble hydrosalpinx and endometriosis. Escherichia coli was detected at higher than normal levels in the menstrual blood of patients with endometriosis in studies of endometrial microbiota [37]. Furthermore, it was reported that levels of bacteria from the Streptococcaceae and Staphylococcaceae families were significantly elevated in the cystic fluid of women with ovarian endometrioma compared with those in controls [38]. Taken together, these results support an association between chronic endometritis and endometriosis [38, 39]. Unfortunately, we did not perform endometrial biopsy to confirm chronic endometritis and endometriosis because our aim was to apply only non-invasive treatment.

Major limitations of the present study were the small sample size and lack of control group. The pregnancy rate was 25% after NIIT combined with assisted reproduction, which was lower than hypothesized. However the sample size is too small for making a judgement about the pregnancy rates. Also we cannot be sure about the naturel improvement of the condition with time since there is not any control group. Another important concern might be management of all patients by the same clinician which can yield a bias in the measurements and assessment of clinical outcomes. We preferred only one author for the management of these patients. Because interobserver variability might yield a a greater bias. Lastly this is a pilot study of an alternative treatment for isthmocele cases and NIIT may represent a new avenue for the treatment of infertility patients with isthmocele.

In conclusion, NIIT could serve as an alternative pretreatment option during IVF cycles for patients with isthmocele. Further prospective controlled studies with larger populations are needed to confirm the utility of NIIT in isthmocele cases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Novafertil IVF Center, for their valuable contributions to all procedures and data gathering.

Financial Disclosure

This study was funded by Novafertil IVF Center Konya Turkey.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consents were obtained from each patient for data analysis.

Author Contributions

ASG contributed to project development and data collection; FG contributed to data collection and manuscript writing; NO contributed to data collection.

Data Avaibility

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Dogum Sekli Tercihinin Multidisipliner Irdelenmesi Calistayi 10-11 Subat 2017 TC Saglik Bakanligi sezeryan verileri.

- Monteagudo A, Carreno C, Timor-Tritsch IE. Saline infusion sonohysterography in nonpregnant women with previous cesarean delivery: the "niche" in the scar. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20(10):1105-1115.

doi pubmed - Bij de Vaate AJ, Brolmann HA, van der Voet LF, van der Slikke JW, Veersema S, Huirne JA. Ultrasound evaluation of the Cesarean scar: relation between a niche and postmenstrual spotting. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(1):93-99.

doi pubmed - Donnez O, Jadoul P, Squifflet J, Donnez J. Laparoscopic repair of wide and deep uterine scar dehiscence after cesarean section. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(4):974-980.

doi pubmed - Naji O, Daemen A, Smith A, Abdallah Y, Saso S, Stalder C, Sayasneh A, et al. Visibility and measurement of cesarean section scars in pregnancy: a reproducibility study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40(5):549-556.

doi pubmed - Tulandi T, Cohen A. Emerging manifestations of cesarean scar defect in reproductive-aged women. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(6):893-902.

doi pubmed - Vervoort AJ, Uittenbogaard LB, Hehenkamp WJ, Brolmann HA, Mol BW, Huirne JA. Why do niches develop in Caesarean uterine scars? Hypotheses on the aetiology of niche development. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(12):2695-2702.

doi pubmed - Rozenberg P, Goffinet F, Phillippe HJ, Nisand I. Ultrasonographic measurement of lower uterine segment to assess risk of defects of scarred uterus. Lancet. 1996;347(8997):281-284.

doi - Vachon-Marceau C, Demers S, Bujold E, Roberge S, Gauthier RJ, Pasquier JC, Girard M, et al. Single versus double-layer uterine closure at cesarean: impact on lower uterine segment thickness at next pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(1):65 e61-65.

doi pubmed - Raimondo G, Grifone G, Raimondo D, Seracchioli R, Scambia G, Masciullo V. Hysteroscopic treatment of symptomatic cesarean-induced isthmocele: a prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(2):297-301.

doi pubmed - Morris H. Surgical pathology of the lower uterine segment caesarean section scar: is the scar a source of clinical symptoms? Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1995;14(1):16-20.

doi pubmed - Morris H. Caesarean scar syndrome. S Afr Med J. 1996;86(12):1558.

- Donnez O, Donnez J, Orellana R, Dolmans MM. Gynecological and obstetrical outcomes after laparoscopic repair of a cesarean scar defect in a series of 38 women. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(1):289-296 e282.

doi pubmed - Gurol-Urganci I, Cromwell DA, Mahmood TA, van der Meulen JH, Templeton A. A population-based cohort study of the effect of Caesarean section on subsequent fertility. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(6):1320-1326.

doi pubmed - Gurol-Urganci I, Bou-Antoun S, Lim CP, Cromwell DA, Mahmood TA, Templeton A, van der Meulen JH. Impact of Caesarean section on subsequent fertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(7):1943-1952.

doi pubmed - Florio P, Filippeschi M, Moncini I, Marra E, Franchini M, Gubbini G. Hysteroscopic treatment of the cesarean-induced isthmocele in restoring infertility. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24(3):180-186.

doi pubmed - Fabres C, Aviles G, De La Jara C, Escalona J, Munoz JF, Mackenna A, Fernandez C, et al. The cesarean delivery scar pouch: clinical implications and diagnostic correlation between transvaginal sonography and hysteroscopy. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22(7):695-700; quiz 701-692.

doi pubmed - Bij de Vaate AJ, van der Voet LF, Naji O, Witmer M, Veersema S, Brolmann HA, Bourne T, et al. Prevalence, potential risk factors for development and symptoms related to the presence of uterine niches following Cesarean section: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(4):372-382.

doi pubmed - Fabres C, Arriagada P, Fernandez C, Mackenna A, Zegers F, Fernandez E. Surgical treatment and follow-up of women with intermenstrual bleeding due to cesarean section scar defect. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(1):25-28.

doi pubmed - Api M, Boza A, Gorgen H, Api O. Should cesarean scar defect be treated laparoscopically? A case report and review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(7):1145-1152.

doi pubmed - Tsuji S, Murakami T, Kimura F, Tanimura S, Kudo M, Shozu M, Narahara H, et al. Management of secondary infertility following cesarean section: Report from the Subcommittee of the Reproductive Endocrinology Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(9):1305-1312.

doi pubmed - Urman B, Arslan T, Aksu S, Taskiran C. Laparoscopic repair of cesarean scar defect "Isthmocele". J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(6):857-858.

doi pubmed - Surrey ES, Silverberg KM, Surrey MW, Schoolcraft WB. Effect of prolonged gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy on the outcome of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(4):699-704.

doi - Sallam HN, Garcia-Velasco JA, Dias S, Arici A. Long-term pituitary down-regulation before in vitro fertilization (IVF) for women with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;1:CD004635.

doi pubmed - Sipahi S, Sasaki K, Miller CE. The minimally invasive approach to the symptomatic isthmocele - what does the literature say? A step-by-step primer on laparoscopic isthmocele - excision and repair. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;29(4):257-265.

doi pubmed - Drouin O, Bergeron T, Beaudry A, Demers S, Roberge S, Bujold E. Ultrasonographic evaluation of uterine scar niche before and after laparoscopic surgical repair: a case report. AJP Rep. 2014;4(2):e65-68.

doi pubmed - Dosedla E, Calda P. Outcomes of Laparoscopic Treatment in Women with Cesarean Scar Syndrome. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:4061-4066.

doi pubmed - Zhang Y. A comparative study of transvaginal repair and laparoscopic repair in the management of patients with previous cesarean scar defect. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(4):535-541.

doi pubmed - Chen Y, Chang Y, Yao S. Transvaginal management of cesarean scar section diverticulum: a novel surgical treatment. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1395-1399.

doi pubmed - Chang Y, Tsai EM, Long CY, Lee CL, Kay N. Resectoscopic treatment combined with sonohysterographic evaluation of women with postmenstrual bleeding as a result of previous cesarean delivery scar defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(4):370 e371-374.

doi pubmed - Tanimura S, Funamoto H, Hosono T, Shitano Y, Nakashima M, Ametani Y, Nakano T. New diagnostic criteria and operative strategy for cesarean scar syndrome: Endoscopic repair for secondary infertility caused by cesarean scar defect. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(9):1363-1369.

doi pubmed - Gubbini G, Casadio P, Marra E. Resectoscopic correction of the "isthmocele" in women with postmenstrual abnormal uterine bleeding and secondary infertility. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(2):172-175.

doi pubmed - Gubbini G, Centini G, Nascetti D, Marra E, Moncini I, Bruni L, Petraglia F, et al. Surgical hysteroscopic treatment of cesarean-induced isthmocele in restoring fertility: prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(2):234-237.

doi pubmed - Taketani Y, Kuo TM, Mizuno M. Comparison of cytokine levels and embryo toxicity in peritoneal fluid in infertile women with untreated or treated endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(1):265-270.

doi - Garzetti GG, Ciavattini A, Provinciali M, Muzzioli M, Di Stefano G, Fabris N. Natural cytotoxicity and GnRH agonist administration in advanced endometriosis: positive modulation on natural killer activity. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88(2):234-240.

doi - Strandell A, Lindhard A. Why does hydrosalpinx reduce fertility? The importance of hydrosalpinx fluid. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1141-1145.

doi pubmed - Khan KN, Kitajima M, Hiraki K, Yamaguchi N, Katamine S, Matsuyama T, Nakashima M, et al. Escherichia coli contamination of menstrual blood and effect of bacterial endotoxin on endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2860-2863 e2861-2863.

doi pubmed - Takebayashi A, Kimura F, Kishi Y, Ishida M, Takahashi A, Yamanaka A, Takahashi K, et al. The association between endometriosis and chronic endometritis. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88354.

doi pubmed - Khan KN, Fujishita A, Masumoto H, Muto H, Kitajima M, Masuzaki H, Kitawaki J. Molecular detection of intrauterine microbial colonization in women with endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;199:69-75.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.