| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Original Article

Volume 11, Number 3, March 2019, pages 188-195

Preoperative Depressive Mood of Patients With Esophageal Cancer Might Delay Recovery From Operation-Related Malnutrition

Yoshihiro Nakamuraa, b, e, Chika Momokia, c, Genya Okadaa, Yoshinari Matsumotoa, Yoko Yasuia, Daiki Habua, Yasunori Matsudad, Shigeru Leed, Harushi Osugid

aDepartment of Nutritional Medicine, Graduate School of Human Life Science, Osaka City University, 3-3-138 Sugimoto, Sumiyoshi-ku, Osaka 558-8585, Japan

bNutritional Control Unit, Treatment Technique Section, Treatment Technique Department, Nagoya City University Hospital, 1 Kawasumi, Mizuho-cho, Mizuho-ku, Nagoya-city, Aichi 467-8602, Japan

cDepartment of Food and Nutrition, Faculty of Contemporary Human Life Science, Tezukayama University, 3-1-3 Gakuenminami, Nara 631-8585, Japan

dDepartment of Gastroenterological Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka City University, 1-4-3 Asahi, Abeno-ku, Osaka 545-8585, Japan

eCorresponding Author: Yoshihiro Nakamura, Nutritional Control Unit, Treatment Technique Section, Treatment Technique Department, Nagoya City University Hospital, 1 Kawasumi, Mizuho-cho, Mizuho-ku, Nagoya-city, Aichi 467-8602, Japan

Manuscript submitted November 29, 2018, accepted December 24, 2018

Short title: Preoperative Depressive Mood of Patients

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr3704

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: We investigated the relationship between the preoperative psychological state and the perioperative nutritional conditions of patients with esophageal cancer.

Methods: Seventy-three participants underwent operations for esophageal cancer in our hospital. Depressive state was evaluated using the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS). General quality of life (QOL) was assessed using the SF-8™, and the nutritional assessments were evaluated through anthropometric analysis, bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) and some biochemical assessments.

Results: In the preoperative stage, patients with higher SDS scores, representing a more depressive state, had low arm circumference, grip strength, serum albumin levels and prognostic nutritional index. Patients with higher SDS scores also had a tendency for a lower physical component summary, representing physical QOL by the Eight-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-8™). At 3 months after surgery, patients with higher preoperative SDS scores had significantly lower body mass indexes (BMIs) and had a lower tendency of body fat masses. In the univariate and multivariate analyses on the recovery of BMI at 3 months after surgery, preoperative SDS score was the only independent risk factor (odd ratio (OR): 4.07, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.15 - 14.35) in this study.

Conclusion: Preoperative depressive mood, as evaluated by the SDS, was the sole relevant factor for postoperative body weight recovery of patients with esophageal cancer. Preoperative depressive mood of patients with esophageal cancer might delay recovery from operation-related malnutrition. Some measures against preoperative depressive mood might be necessary for early recovery from postoperative malnutrition in patients with esophageal cancer.

Keywords: Esophageal cancer; Depressive mood; Nutritional status after surgery

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Unfeigned cancer notification sometimes causes severe psychological and/or physiological damage in patients with cancer. Any patients with cancer might have some degree of anxiety about disease progression or prognosis as well as anger and depressive mood after being notified by their doctors that they have cancer. It was reported that the most common psychological problem was depressive state in patients with cancer [1, 2]. Depressive state due to cancer notification might affect patient nutritional condition [3, 4]. Improvement of preoperative psychological condition may be essential for early recovery from heavily invasive surgeries such as esophagectomy. Esophagectomy is thought to be the most invasive surgery for gastrointestinal cancers, because, in addition to the tumor dissection, this surgery involves a wide operative field that includes the neck, chest and abdomen as well as lymph node dissection. The purpose of this study is to analyze the relationship between preoperative psychological conditions and postoperative nutritional recovery in patients with esophageal cancer.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design and participants

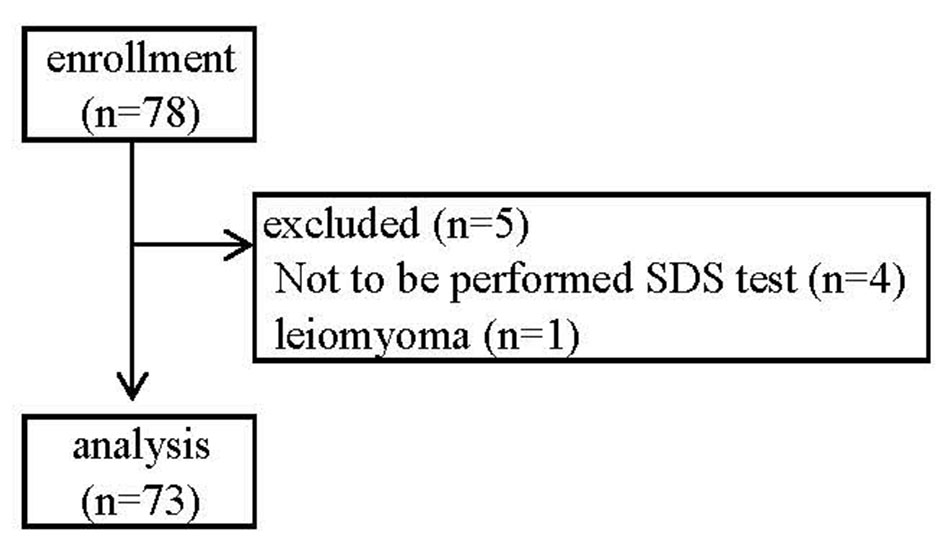

This study was a cohort study. A total of 78 patients at our hospital were enrolled in this study between June 1, 2009, and December 31, 2011. Five patients were excluded from the study because they did not undergo Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) test or were diagnosed with leiomyoma (Fig. 1). Fifty-four were men and 19 were women with an average age of 63.6 ± 8.8 years. All patients were diagnosed with esophageal cancer and underwent esophagectomy (thoracoscopic laparotomy or thoracolaparotomy and enterostomy). Patients were surveyed preoperatively and postoperatively at 3 and 6 months. All of them agreed to participant in this study voluntarily and gave written informed consent.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Flow diagram according to selection and non-continuation. |

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions.

Classification according to the SDS

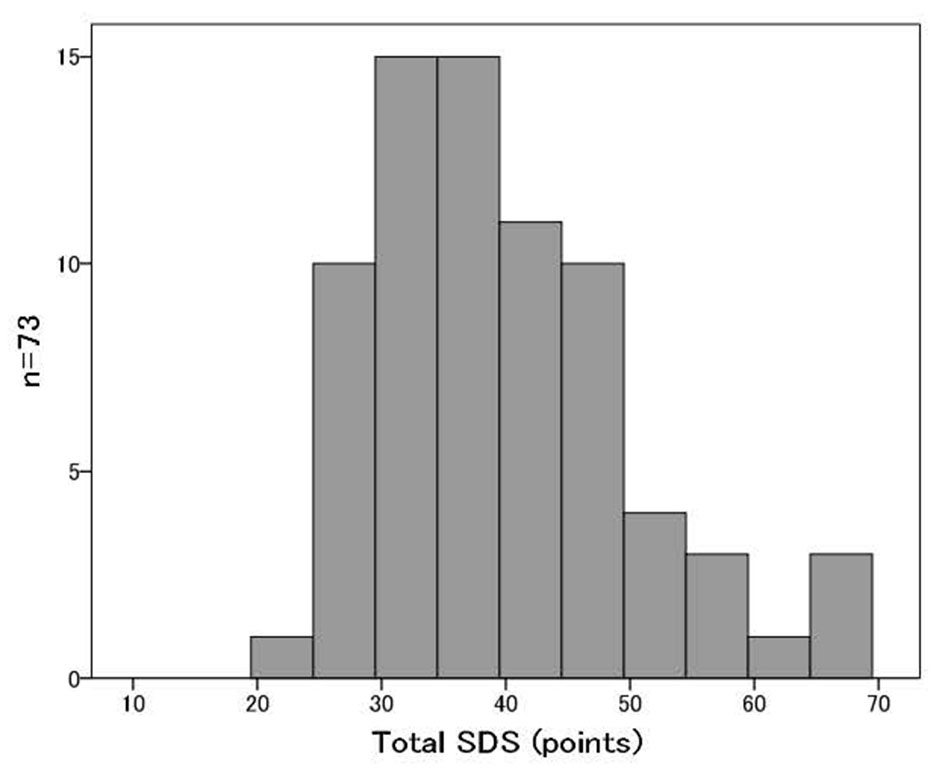

A total of 73 patients with esophageal cancer were divided into two study groups based on their SDS scores [5]. Those with total SDS scores lower than 39 were placed in the normal group (normal SDS group), and those with total SDS scores of 39 or more were placed in the depressive group (high SDS group). We defined the cutoff value of SDS as 39 points in this cohort for the following two reasons: first, the median SDS of this cohort was 39 points (Fig. 2); and second, the mean SDS score for the Japanese general population was 39.3 points in a previous large scaled cross-sectional study [6]. We compared their health-related quality of life (QOL) as determined by a Japanese-validated version of the Eight-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-8™), anthropometries, body composition date as determined by InBody S430 (InBody Japan Co., Ltd) and biochemical data at preoperative stage and postoperative stages of 3 and 6 months after surgery in this two groups.

Click for large image | Figure 2. The distribution of SDS scores of all patients. |

We adopted the SF-8™ to assess the health-related quality of life of patients. This score can be compared to the Japanese normative sample scores of the SF-8™. The SF-8™ is an eight-item questionnaire that calculates eight physical and mental health domains: physical functioning (PF), role-physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role-emotional (RE) and mental health (MH). The physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS) were calculated based on the sum of the scores of the corresponding subscales: PF, RP, BP and GH for PCS, and VT, SF, RE and MH for MCS. PCS and MCS in the SF-8™ were expressed as the median percentage of Japanese healthy men and women, respectively [7-10].

Anthropometry and body composition

Each patient’s height, preoperative weight, arm circumference (AC), triceps skinfold (TSF) and grip strength were measured during the nutritional status evaluation. The body mass index (BMI), arm muscle circumference (AMC) and arm muscle area (AMA) were subsequently calculated. All data were expressed as % of median of Japanese healthy individuals quoted from Japanese Anthropometric Reference Data (JARD 2001) [11].

InBody 430 (InBody Japan Co., Ltd) was used to perform body composition analysis (body weight, BMI, skeletal muscle volume and body fat). These data were expressed as % of median of Asian healthy individuals (data were presented by InBody Japan Co., Ltd).

The mean values of both hand grip strength measurements were expressed as a percentage by dividing the average of each age acquired from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, which performed a test of physical strength and Ex capacity in 2009.

Laboratory data and nutritional status assessment

To evaluate nutritional status, data were collected for the following parameters: white blood cell count (WBC), total lymphocyte count (TLC), C-reactive protein (CRP), albumin (Alb), cholinesterase (ChE), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (T-Chol), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-Cho), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-Cho) and transthyretin (TTR).

To assess nutritional status, the prognostic nutritional index (PNI) [12] and creatinine height index [%] (CHI) [13] were used. PNI and CHI were calculated using the following formulae:

PNI = 10 × Alb + 0.005 × TLC

CHI = measured 24-h urinary creatinine ×100/normal 24-h urinary creatinine

Statistical analysis

The outcomes are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR), numbers of patients or percentages. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables among the two groups.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression modeling was used to identify the relevant factors for recovery of %BMI as 85% or more at 3 months after surgery; 85% of %BMI was nearly equal to 18.5 kg/m2 of BMI, which represented the cutoff value of emaciation or malnutrition. Therefore, we defined 85% of %BMI, nearly equal to 18.5 kg/m2 of BMI or more at 3 months after surgery, as indicating recovery from critical malnutrition due to esophagectomy. Sex (male versus female), age (< 65 years versus ≥ 65 years), cancer stage (stages I - II versus stages III - V), chemotherapy (absence versus prescription), SDS score (< 39 versus ≥ 39) and PNI score (< 49 versus ≥ 49) were chosen as potential factors. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression modeling was used to obtain the crude and adjusted odd ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the association between each factor and recovery of %BMI as 85% or more at 3 months after surgery.

SPSS statistical software for Windows (version 22; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for analytical comparisons of the two groups. SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for the univariate and multivariate analyses. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

| Results | ▴Top |

We divided the participants in to two groups. The normal SDS group contained 36 patients, and the high SDS group contained 37 patients. The patients’ preoperative characteristics and nutritional status details are listed in Table 1. The high SDS group had significantly higher total SDS scores (median value: 46 points, P < 0.001), lower BMI (median value: 19.8 kg/m2, P = 0.007), younger than normal SDS group and lower percentage of men (n = 23, 62%, P = 0.032) than did the normal SDS group.

Click to view | Table 1. Patients’ Preoperative Characteristics |

We compared the results in these two groups on each item of the SDS (Table 2) and SF-8 (Table 3), body compositions and anthropometries (Table 4), and laboratory data (Table 5). As for respective items of the SDS, excluding only question number 19 about suicidal ideation, the high SDS group had significantly higher scores than did the normal SDS group in all other items (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Score of Each SDS Item Before Surgery |

Click to view | Table 3. Comparison of SF-8 Between the Two Groups |

Click to view | Table 4. Comparison of Body Composition and Anthropometries Between the Two Groups |

Click to view | Table 5. Comparison of Preoperative Laboratory Data and Nutritional Status Assessment Between the Two Groups |

On QOL by SF-8™, the high SDS group had significantly lower %PCS (median value: 95.1, P = 0.024), which means physical QOL, than did the normal SDS group. Additionally, the %PCS of the high SDS group was lower than that of the median for Japanese healthy individuals (Table 3).

As for body compositions and anthropometries, the high SDS group had significantly lower %BMI (P = 0.015), %skeletal muscle volume (P = 0.036), %AC (P = 0.022), %AMA (P = 0.033) and %grip strength (P = 0.012) than did the normal SDS group (Table 4). As for laboratory data, the high SDS group had significantly lower TLC, Alb and TTR (P = 0.041, 0.018 and 0.009, respectively) than in the normal SDS group. The high SDS group also had lower PNI scores (median value: 46.9, P = 0.007) than did the normal SDS group. However, there was no significant difference on CHI between the two groups (Table 5).

We analyzed the following items sequentially preoperatively and at 3 and 6 months after surgery (Table 6). As for the SDS, the high SDS group had consistently higher scores than did the normal SDS group throughout the observation period. As for QOL by SF-8™, only in preoperative %PCS, the high SDS group had significantly lower scores (median value: 89.3, P = 0.023) than did the normal SDS group. In other points, there were no significant differences between these two groups on either %PCS or %MCS; %BMI continued to decrease from the preoperative period (normal group: 99.8%, high group: 91.2%) to 6 months (89.1% and 78.9%, respectively) after surgery in both groups. The high SDS group had significantly lower %BMI than did the normal SDS group preoperatively and at 3 and 6 months postoperatively. Regarding anthropometric data, such as %skeletal muscle volume and %body fat, the results showed similar tendency to %BWI, too. However, only %grip strength increased from 3 months to 6 months after operation in both groups.

Click to view | Table 6. Changes in Variables at 3 and 6 Months Among Two SDS Groups |

Table 7 shows the results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression modeling, which were used to determine the relevant factors for the recovery of %BMI as 85% or more at 3 months after surgery. Fifty-one patients who could be fully checked for relevant factors were analyzed. Unadjusted univariate logistic regression modeling suggested that only two factors, SDS scores (OR: 4.38, 95% CI: 1.31 - 14.68) and PNI scores (OR: 3.77, 95% CI: 1.14 - 12.46), were significantly associated with the recovery of %BMI. In the multivariate logistic regression modeling included for SDS score and PNI score, SDS score alone was significantly associated with the recovery of %BMI. The OR of SDS score for the recovery of %BMI was 4.07 (95% CI: 1.15 - 14.35).

Click to view | Table 7. Univariate and Multivariate ORs and 95% CIs for Association Recovery of %BMI as 85% or More at 3 Months after Surgery |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

We tried to analyze the relationship between preoperative depressive mood due to unfeigned cancer notification and preoperative and postoperative nutritional states in patients with esophageal cancer. Almost half of the participants in this study were judged as having depressive state as evaluated by the SDS just before surgery (cutoff value of SDS: 39 point). The reasons for their depressive state might be that they thought that esophageal cancer was highly malignant with a poor prognosis and that the surgery for this disease was very invasive.

When it comes to the gender difference, we believe that the women in this cohort tended to have higher SDS scores than men did for the following reasons. First, in the high SDS group, women accounted for 37.8% (14/37), while in the normal SDS group, women only accounted for 13.9 (5/36) (Table 1). Second, women had higher SDS scores (median value: 42 points) than men (median value: 37 points) (P = 0.017) as a whole in this cohort.

The high SDS group also had lower PNI scores (median value: 46.9, P = 0.007) than did the normal SDS group. In a previous report, the truth disclosure was associated with physical symptoms in patients with lung cancer [14]. Patients with depressive state due to notification of cancer frequently had somatic disorders such as general fatigue or body pain [15]. Therefore, these patients might experience more difficulties in physical conditions than in psychological conditions.

As for body compositions and anthropometries, the depressive group tended to show lower %BMI, %skeletal muscle volume and %grip strength in both preoperative and postoperative stages. As for the SDS, the depressive group showed continuously higher SDS scores than the normal group through perioperative period. Preoperative depressive state in patients with esophageal cancer seemed to remain for a rather long period. Lower physical activities in these patients due to depressive state might affect their postoperative physical conditions [16-18]. Although in the postoperative stage, there was no significant difference between the groups on %PCS, the depressive group showed lower values in anthropometries associated with skeletal muscles. If elderly patients in the depressive group might have difficulties in ordinary life due to muscle atrophy, they might not be aware of those symptoms. Therefore, we may pay more attention to those patients in terms of their difficulties in ordinary life.

The depressive group showed worse biochemical nutritional assessments such as TLC, Alb, TTR and PNI in the preoperative stage. In previous reports [19-21], one of the relevant factors for malnutrition was depressive state, and patients with depressive mood tended to have lower values of serum total protein and Alb. Depressive mood might affect the appetite in these patents, lead to reduce the food intake and cause lower biochemical values representing their nutritional conditions.

In the univariate and multivariate analyses of the recovery of BMI at 3 months after surgery, preoperative SDS score was the only independent risk factor in this study. In other words, patients with preoperative depressive state tended to have difficulty recovering the nutritional condition represented by body weight at 3 months after surgery. In previous reports, depressive mental status was significantly related to nutritional conditions in patients with cancer [18] and community-dwelling elderly individuals [21].

In summary, there were more than a few patients with depressive state probably due to notification of esophageal cancer in the preoperative stage, and these depressive mental states might contribute to the poor nutritional conditions before surgery. This preoperative mental status might negatively affect the recovery of their nutritional conditions and their QOL after surgery. From these findings, in patients with preoperative depressive state, we might consider consulting psychiatrists or clinical psychotherapists to improve their mental states and then improve their nutritional conditions in both pre- and postoperative stages.

We considered potential limitations of this study. First, our study had a relatively small sample size and a short follow-up period. A prospective study with a large sample size may be warranted in the future. Second, our study did not investigate nutrient intakes from diagnosis to perioperative period and, therefore, we could not identify an association between perioperative nutrient intake and nutritional status. These issues will be addressed in a future study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we should give more attention to the preoperative mental status of patients with esophageal cancer to improve their pre- and postoperative nutritional conditions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the individuals who participated in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Author Contributions

Yoshihiro Nakamura, Chika Momoki and Daiki Habu were responsible for study conception and design. Yasunori Matsuda, Shigeru Lee and Harushi Osugi were responsible for acquisition. Genya Okada, Yoshinari Matsumoto and Yoko Yasui were responsible for acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Yoshihiro Nakamura, Chika Momoki and Daiki Habu were responsible for critical revision.

| References | ▴Top |

- Massie MJ, Holland JC. The cancer patient with pain: psychiatric complications and their management. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1992;7(2):99-109.

doi - Ina K, Sugiyama A, Yuasa S, Koga C, Yamazaki E, Katayama Y, Nagaoka M, et al. [Depression screening test for patients with metastatic gastric and colorectal cancer]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2010;37(6):1059-1063.

pubmed - Duc S, Rainfray M, Soubeyran P, Fonck M, Blanc JF, Ceccaldi J, Cany L, et al. Predictive factors of depressive symptoms of elderly patients with cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy. Psychooncology. 2017;26(1):15-21.

doi pubmed - Naidoo I, Charlton KE, Esterhuizen TM, Cassim B. High risk of malnutrition associated with depressive symptoms in older South Africans living in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a cross-sectional survey. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;33:19.

doi pubmed - Tetsunaga T, Misawa H, Tanaka M, Sugimoto Y, Tetsunaga T, Takigawa T, Ozaki T. The clinical manifestations of lumbar disease are correlated with self-rating depression scale scores. J Orthop Sci. 2013;18(3):374-379.

doi pubmed - Chida F, Okayama A, Nishi N, Sakai A. Factor analysis of Zung Scale scores in a Japanese general population. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58(4):420-426.

doi pubmed - Fukuhara S, Suzukamo Y. Manual of the SF - 8 Japanese Version (in Japanese). Kyoto: Institute for Health Outcomes and Process Evaluation Research, 2004. http://webcatplus.nii.ac.jp/webcatplus/details/book/11341988.html

- Shiozaki M, Hirai K, Dohke R, et al. Measuring the regret of bereaved family members regarding the decision to admit cancer patients to palliative care units. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:1142-1147.

- Shibata A, Oka K, Nakamura Y, Muraoka I. Recommended level of physical activity and health-related quality of life among Japanese adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:64.

doi pubmed - Uramoto H, Kagami S, Iwashige A, Tsukada J. Evaluation of the quality of life between inpatients and outpatients receiving cancer chemotherapy in Japan. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(2):1127-1132.

pubmed - Japanese Society of Nutritional Assessment. Japanese Anthropometric Reference Data (JARD2001). Journal of Nutritional Assessment. 2002;19(Suppl):1-81 (in Japanese).

- Maeda K, Nagahara H, Shibutani M, Otani H, Sakurai K, Toyokawa T, Tanaka H, et al. A preoperative low nutritional prognostic index correlates with the incidence of incisional surgical site infections after bowel resection in patients with Crohn’s disease. Surg Today. 2015;45(11):1366-1372.

doi pubmed - Viteri FE, Alvarado J. The creatinine height index: its use in the estimation of the degree of protein depletion and repletion in protein calorie malnourished children. Pediatrics. 1970;46(5):696-706.

pubmed - Saitoh E, Yokomizo Y, Chang CH, Eremenco S, Kaneko H, Kobayashi K. Cross-cultural validation of the Japanese version of the lung cancer subscale on the functional assessment of cancer therapy-lung. J Nippon Med Sch. 2007;74(6):402-408.

doi pubmed - Hashimoto N, Isaka N, Ishizawa Y, Mitsui T, Sasaki M. Surgical management of colorectal cancer in patients with psychiatric disorders. Surg Today. 2009;39(5):393-398.

doi pubmed - Matsushita T, Matsushima E, Maruyama M. Assessment of peri-operative quality of life in patients undergoing surgery for gastrointestinal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12(5):319-325.

doi pubmed - Matsushita T, Matsushima E, Maruyama M. Anxiety and depression of patients with digestive cancer. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):576-583.

doi pubmed - Tian J, Chen ZC, Hang LF. Effects of nutritional and psychological status in gastrointestinal cancer patients on tolerance of treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(30):4136-4140.

doi pubmed - Ulger Z, Halil M, Kalan I, Yavuz BB, Cankurtaran M, Gungor E, Ariogul S. Comprehensive assessment of malnutrition risk and related factors in a large group of community-dwelling older adults. Clin Nutr. 2010;29(4):507-511.

doi pubmed - Maes M, Wauters A, Neels H, Scharpe S, Van Gastel A, D’Hondt P, Peeters D, et al. Total serum protein and serum protein fractions in depression: relationships to depressive symptoms and glucocorticoid activity. J Affect Disord. 1995;34(1):61-69.

doi - Iizaka S, Tadaka E, Sanada H. Comprehensive assessment of nutritional status and associated factors in the healthy, community-dwelling elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2008;8(1):24-31.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.