| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Original Article

Volume 10, Number 9, September 2018, pages 688-692

Vulvovestibular Syndrome and Vaginal Microbiome: A Simple Evaluation

Maria Vadalaa, b, f, Christian Testac, Laura Codad, Stefania Angiolettic, Rosanna Giubertie, Carmen Laurinoa, b, Beniamino Palmieria, b

aDepartment of General Surgery and Surgical Specialties, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia Medical School, Surgical Clinic, Via del Pozzo, 71, 41124 Modena, Italy

bSecond Opinion Medical Network, Via del Pozzo, 71, 41124 Modena, Italy

cFunctionalpoint srl, Via dell’ Industria, 7, 24126 Bergamo, Italy

dHealth Center Ginecea, Milano, Italy

eSocieta italiana di idrocolon terapia (ICT), Milano, Italy

fCorresponding Author: Maria Vadala, Department of General Surgery and Surgical Specialties, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia Medical School, Surgical Clinic, Modena, Italy

Manuscript submitted May 15, 2018, accepted June 20, 2018

Short title: Vulvovestibular Syndrome and Vaginal Microbiome

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr3480w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: The vulvovestibular syndrome (VVS) is a chronic, inflammatory, multifactorial, chronic inflammation of the female urogenital access.

Methods: The aim of this anecdotal, observational, retrospective, case-control study was to comparatively evaluate the most common bacterial strains (Lactobacillus spp., Klebsiella spp., Gardnerella spp., and Streptococcus spp.) and fungi (Candida spp., Pennicillum spp., and Aspergillus spp.) in vulvodinic women, and in women without gynecological symptoms (control group).

Results: We found that vulvodinic patients had statistically lower Lactobacilli and higher total Fungi concentration.

Conclusions: Our preliminary study is useful to further clarify the etiopathology of vulvodynia and suggest new therapeutic strategies for approaching the VVS.

Keywords: VVS; Vulvodinic; Lactobacilli; Fungi; Bacteria; Women

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Vulvovestibular syndrome (VVS) or vulvodynia or vestibulodynia, is a worldwide spread chronic syndrome of unknown etiology that affects approximately 20-30% of the women, with moderate/severe life quality impairment due to chronic submucosa vulvar inflammation in the vulvar vestibule area, which is often ulcerated with burning pain, edema and erythema [1].

In the 2015, the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD), the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH), and the International Pelvic Pain Society (IPPS) defined, during an international meeting, the vulvodynia as “vulvar discomfort, most often described as burning pain of at least 3 months duration, occurring in the absence of relevant visible findings or a specific, clinically identifiable, neurologic disorder” [2].

The patients complain vaginal discharge or vaginal dryness and pelvic floor muscle hypertonicity, with positivity to cotton swab test and/or Friedrich’s three diagnostic criteria (severe pain on vestibular touch, tenderness to pressure localized within the vulvar vestibule, and vestibular erythema of various degrees) [3, 4]. The VVS is thus included in neuropathic pain group, where the nerve endings network of the submucosal vestibular space named “peripheral awareness”, causes hyperalgesia (an exaggerated response to a painful stimulus) and allodynia (pain due to application of a normally non-painful stimulus) [5].

However, the risk factors associated with this clinical condition can be endogenous (e.g. pregnancy and lactation, yeast or other genital tract infection, variations in hormone levels) or exogenous (e.g. sexual intercourse with a specific partner, oral contraceptives, vaginal surgery or laser treatment, smoking, stress) triggers that could induce a chronic localized stimulation and/or proliferation of the peripheral nerve fibers in the vestibule, resulting in an increased local sensitivity [6, 7].

The healthy vaginal microbiota with predominant Lactobacillus spp. (107 to 108 colony forming units (CFU)/g of vaginal fluid in premenopausal woman) is putatively stated as milestone against bacterial vaginosis, yeast infections, sexually transmitted infections, urinary tract infections and HIV infection [8, 9]. In fact, the lactic acid produced by Lactobacilli and present in two different isomers (L-and D-lactic acid) has antimicrobial, antiviral and immunomodulatory properties: lowering variably the environmental pH; dampening pro-inflammatory responses elicited by Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists from cervico-vaginal epithelial cells, producing antimicrobial compounds (e.g. H2O2, bacteriocins) that inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria, including Salmonella, Chlamydia, and Trichomonas [10-19]. The L-lactic acid, which is produced by both bacteria and vaginal epithelial cells, can induce release of pro-inflammatory cytokines by vaginal epithelial cells. Also, the D-lactic acid (produced mainly by bacteria) is supposed to have some role not yet adequately investigated in this syndrome [20]. Several studies on the microbiome in VVS patients showed a prevalence of Streptococcus, Gardnerella, Enterococcus, and Candida albicans spp. [7-22].

The aim of this observational, retrospective, case-control study was to assess the vaginal flora in patients affected by chronic VVS, compared with the pattern of the healthy, asymptomatic women (control group), working on the hypothesis that some vaginal infection bacterial or mycotic could be a risk factor for the onset of VVS.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

A total of 50 women (aged 19 and 45 years) affected by symptomatic vulvodynia, including burning pain, edema and erythema of the vulvar vestibule, resulting vulvovaginal dryness and hypertonic pelvic floor since at least 6 months, spontaneously appealed to our “Second Opinion Medical Consulting Network” (Modena, Italy) (Table 1). The Second Opinion Medical Network is a consultation referral web and Medical Office System recruiting suddenly a wide panel of real-time available specialists, to whom any patient affected by any disease or syndrome and not adequately satisfied by the diagnosis or therapy can apply for an individual clinical audit [23].

Click to view | Table 1. Patient’s Characteristics |

All the enrolled patients had dyspareunia treated with different topical and/or systemic therapies with little or no benefit (wash out period of previous therapies for up to 20 days).

The VVS diagnosis was confirmed through the swab test, performed with a cotton swab touched to the vaginal vestibule, and the degree of erythema is determined by visual inspection of the vulvovaginal glandular outlets by the examiner, the higher the score, the more severe the symptoms.

The quantification of the intensity of the pain is determined by the numeric rating scale (NRS) which scored the intensity of the symptoms: each patient, during the visit, is asked to indicate, with a number, the pain severity: from 0 (no pain) until 10 (most intense pain imaginable).

The hypertonia of anus elevator muscle is evaluated either manually (subjective perception) or by electromyographic biofeedback (BFB), through a vaginal probe into the anus, transducing electromagnetic signals to a specific software (following Spano’s method) [24]. In this observational, retrospective, case-control study, we adopted some well-defined exclusion criteria: 1) pregnant or lactating women, 2) women with ongoing antifungal, antibiotic or antiviral therapy, 3) women using oral contraceptives, and 4) women using vaginal diazepam suppositories for high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.

We included 50 healthy women of childbearing age, with no previous medical history of vulvodynia and no complaints, problems or current or past infection in the genital tract (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of Enrolled Patients |

The intestinal flora was screened about Bacteria and Candida positive in stool samples on plates, accordingly with American Society of Clinical Microbiology [25]. The fecal samples of VVS and health patients were collected in transport medium with specific sticker. Subsequently, the bacterial flora was evaluated after 48 h of incubation under appropriate conditions using a selective agar plate. In particular, we used LBS Selective Agar (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) for Lactobacilli; -CHROMagar Orientation (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) for Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp, and Enterococcus spp; -Orientation CHROMagar Candida (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) for Candida spp; and -Saburaud Glucose Agar (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) for the Fungi.

A further metabolic test on organisms isolated by the identification system of Cristal BBL (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) was added to the screening. The test coefficient of variation was < 9%. The results are being expressed in colony forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) of stool. The test was performed by Functional Point Laboratory (Bergamo, Italy), a clinical and virology laboratory that adheres to international quality control standards and is accredited as an official laboratory within the National Health System.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at a P value < 0.05, and all data and graphics were analyzed using the R software, version 3.1.2 [26].

| Results | ▴Top |

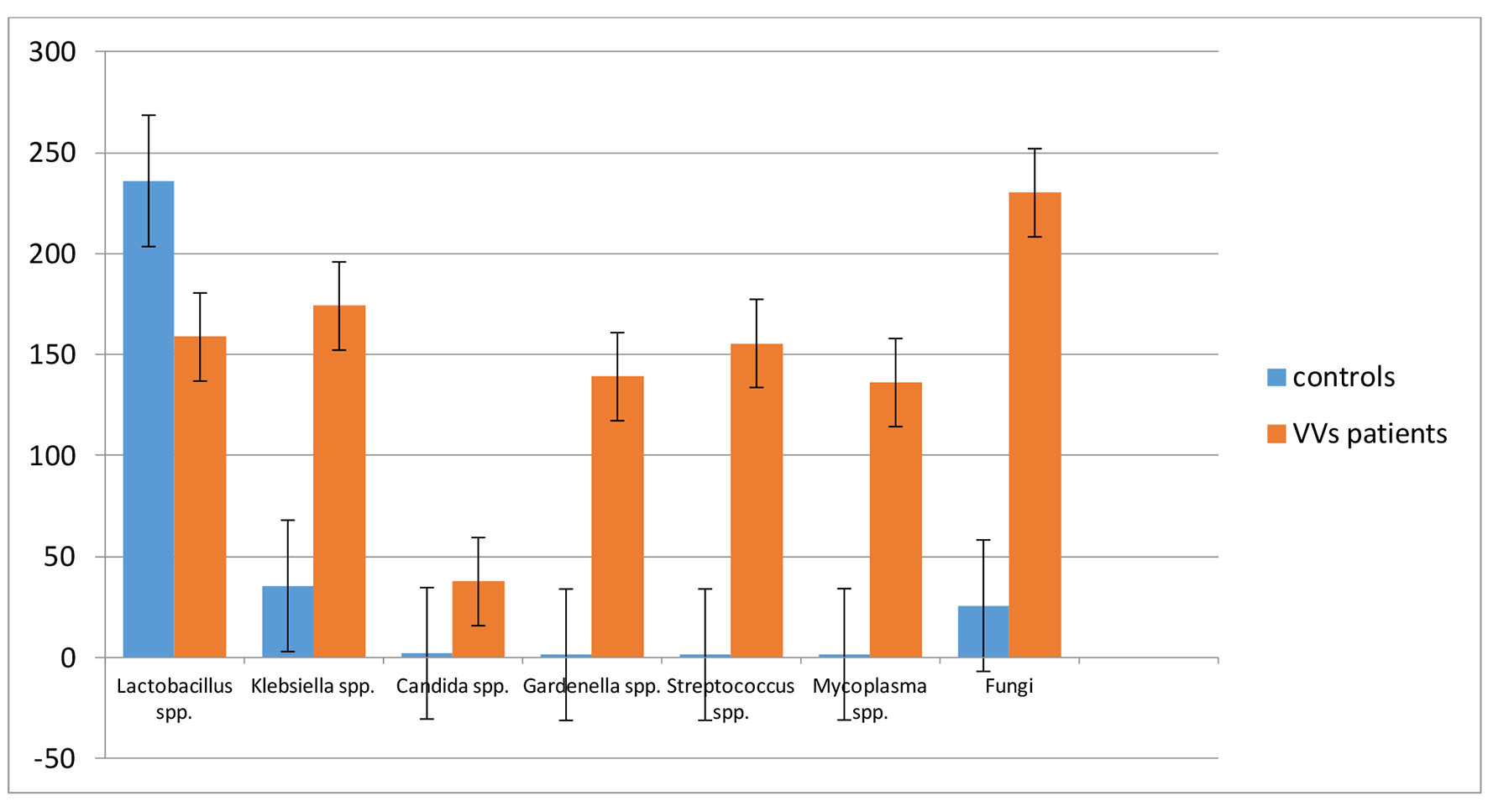

The results of bacterial isolations were expressed in colony forming units (CFU)/mL (Table 3). The selected Fungi belonged, in all the samples, to the genera of Aspergillus and Pennicillum spp. The Lactobacilli were significantly (P < 0.05) reduced in VVS patients, compared to the health women (controls). Conversely the microbiological charge of Klebsiella, Candida and Fungi spp. were significantly (P < 0.05) higher in the VVS population compared to the control group. We extended the study to Gardenerella, Streptococcus spp. and Mycoplasma that were dominant in the samples of symptomatic women (Fig. 1).

Click to view | Table 3. Bacterial Species in the Health Patients (Controls) and in VVS Patients |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Comparison of bacterial population in the studied clinical cases. The value is expressed in CFU/mL ± SD. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Several studies evidenced the doctor-patient communication gap, and the increasing number of patients that usually wander around the medical websites looking for proper answers to their health problems [27, 28]. However, their search often becomes compulsive and obsessive and often ambiguous and frustrating [29]. Palmieri et al [30] describe this borderline or even pathological behavior as the “Web Babel Syndrome” - a psychological imbalance affecting young and elderly patients, especially those with multiple synchronous diseases who receive from their caregivers heterogeneous and misleading informations or advices, including confused, contradictory statements and prescriptions [31]. To deal with this problem, the Second Opinion Network aims to be a useful “problem-solving” support revisiting each diagnostic and therapeutic step and properly re-addressing tailored treatments and prognoses, as well as preventing unnecessary investigational procedures and unhelpful and expensive medical and surgical interventions, such as the diagnosis, risk factors, pathological mechanism and therapy of VVS [32].

In the clinical expression of VVS, many pathological mechanisms are involved [22]. The inflammatory aspect has a key role in generating the main symptoms of this syndrome [33]. The correlation between the immune system and bacteria is significant: the poor growth of Lactobacilli can suggest a pro-inflammatory immune background; the overgrowth of Klebsiella spp. is a probable responsible of pathological condition associated with VVS. The elevated detection of Streptococcus spp. in the women with VVS may also be involved in these mechanisms. This microorganism, which also produces lactic acid, is usually found at low levels in apparently healthy women, while high vaginal concentrations have been associated with a clinical condition known as aerobic vaginitis [34]. In addition, a case report evidenced an association of group B Streptococcus with vulvar pain, common VVS symptom [35]. Ventolini et al, in a preliminary clinical trial, hypothesized a vaginal flora alteration and an immunological response involving Candida albicans in VVS patients [36]. Indeed, they reported an increase of IL-17 in patients with vaginal candidiasis, reaching their pick 14 days after the infection, and a decrease of interleukin-12 (IL-12) and seven-fold of the macrophage inflammatory protein 1 beta (Mip-Ib) in post-infection due to Candida a. These data suggest that the Candida superinfection might be the first cause of vulvodynia symptom or as immunological response in VVS. Accordingly, with previous animal models investigation where the seeding of fungi in the vaginal flora induced a local and systemic inflammatory state [36, 37]. The fungal flora in our case-control study is represented by Candida, Aspergillus and Pennicillum spp. and since is significantly altered, it is reasonably supposed to trigger or boost the organ dysfunction.

The use of probiotics to populate the vagina and prevent or treat this alteration has been, in the past, anecdotally reported, but only recently we have an evidence-based clinical benefit of their administrations with supplementation of antimicrobial treatment to improve cure rates and prevent recurrences. It has been known that Lactobacilli produce bacteriocins that can inhibit the growth of pathogens, including some associated with bacterial vaginosis, such as Gardnerella vaginalis [38]. Indeed, Mastromarino et al [39] found, in vitro, that Lactobacillus gasseri 335 and Lactobacillus salivarius FV2 were able to coaggregate with Gardnerella v. When these strains of Lactobacilli were combined with Lactobacillus brevis CD2 in a vaginal tablet, adhesion of Gardnerella v. was reduced by 57.7%, and 60.8% of adherent cells were displaced. Boris et al found that the adherent properties Gardnerella v. were similarly affected by Lactobacillus acidophilus [40]. Cauci et al observed also that vaginal concentrations of IL-1β were higher in women whose vaginal microbiota was dominated by Gardnerella spp., supposing a pro-inflammatory immunity, induced by the association between vaginal IL-1β levels and bacterial vaginosis, often characterized by increased concentration in Gardnerella and reduced concentration of Lactobacilli [41].

Another effective method for reducing the bacterial burden and the microbiota imbalance is the vaginal irrigation with carbonated saline by Palmieri et al [42], who investigated the therapeutic effect of 7% CO2 enriched water washout (250 mL saline plus CO2 volume protocol) in 40 women complaining, in the last 3 years, vaginosis and vaginitis, daily for 2 weeks of treatment. The outcomes reported definitive symptoms improvement (reduction of burning pain, itching) in 15 patients after 6 days, 10 in 4 days and two in 2 days.

Conclusions

Our preliminary data suggest a role of the fungal pathogenic flora and reduced Lactobacilli population in vulvodinic patients and stimulate further options of local and systemic medical treatments.

| References | ▴Top |

- Harlow BL, Stewart e G. A Population-Based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we under estimated-the prevalence of vulvodynia? J AM Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58:82-88.

- Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, Bergeron S, Pukall C, Zolnoun D, Coady D, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS consensus terminology and classification of persistent vulvar pain and vulvodynia. J Sex Med. 2016;13(4):607-612.

doi pubmed - Goetsch MF. Vulvar vestibulitis: prevalence and historic features in a general gynecologic practice population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164(6 Pt 1):1609-1614; discussion 1614-1606.

- Friedrich EG, Jr. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1987;32(2):110-114.

pubmed - Glazer HI, Jantos M, Hartmann EH, Swencionis C. Electromyographic comparisons of the pelvic floor in women with dysesthetic vulvodynia and asymptomatic women. J Reprod Med. 1998;43(11):959-962.

pubmed - May S, Serpell M. Diagnosis and assessment of neuropathic pain. F1000 Med Rep. 2009;1:76.

doi - Witkin SS. The microbiome of the vagina and vestibule. Spring. 2015;XIX(I):10-12.

- Jayaram A, Witkin SS, Zhou X, Brown CJ, Rey GE, Linhares IM, Ledger WJ, et al. The bacterial microbiome in paired vaginal and vestibular samples from women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Pathog Dis. 2014;72(3):161-166.

doi - Donders GG, Bosmans E, Dekeersmaecker A, Vereecken A, Van Bulck B, Spitz B. Pathogenesis of abnormal vaginal bacterial flora. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(4):872-878.

doi - Barbes C, Boris S. Potential role of lactobacilli as prophylactic agents against genital pathogens. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 1999;13(12):747-751.

doi pubmed - Gupta K, Stapleton AE, Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Fennell CL, Stamm WE. Inverse association of H2O2-producing lactobacilli and vaginal Escherichia coli colonization in women with recurrent urinary tract infections. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(2):446-450.

doi pubmed - Pybus V, Onderdonk AB. Microbial interactions in the vaginal ecosystem, with emphasis on the pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis. Microbes Infect. 1999;1(4):285-292.

doi - Martin HL, Richardson BA, Nyange PM, Lavreys L, Hillier SL, Chohan B, Mandaliya K, et al. Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(6):1863-1868.

doi pubmed - Sobel JD. Is there a protective role for vaginal flora? Curr Infect Dis Rep. 1999;1(4):379-383.

doi pubmed - Boskey ER. Vaginal acidity is produced by vaginal bacteria. PhD thesis (The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore), 2000.

- Boskey ER, Cone RA, Whaley KJ, Moench TR. Origins of vaginal acidity: high D/L lactate ratio is consistent with bacteria being the primary source. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(9):1809-1813.

doi pubmed - Kaewsrichan J, Peeyananjarassri K, Kongprasertkit J. Selection and identification of anaerobic lactobacilli producing inhibitory compounds against vaginal pathogens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;48(1):75-83.

doi pubmed - Klebanoff SJ, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA, Waltersdorph AM. Control of the microbial flora of the vagina by H2O2-generating lactobacilli. J Infect Dis. 1991;164(1):94-100.

doi pubmed - Voravuthikunchai SP, Bilasoi S, Supamala O. Antagonistic activity against pathogenic bacteria by human vaginal lactobacilli. Anaerobe. 2006;12(5-6):221-226.

doi pubmed - Tachedjian G, Aldunate M, Bradshaw CS, Cone RA. The role of lactic acid production by probiotic Lactobacillus species in vaginal health. Res Microbiol. 2017;168(9-10):782-792.

doi pubmed - Beghini J, Linhares IM, Giraldo PC, Ledger WJ, Witkin SS. Differential expression of lactic acid isomers, extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer, and matrix metalloproteinase-8 in vaginal fluid from women with vaginal disorders. BJOG. 2015;122(12):1580-1585.

doi pubmed - Havemann LM, Cool DR, Gagneux P, Markey MP, Yaklic JL, Maxwell RA, Iyer A, et al. Vulvodynia: what we know and where we should be going. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2017;21(2):150-156.

doi pubmed - Wunsch A, Palmieri B. The role of second opinion in oncology: an update. Eur J Oncol. 2013;18(3):3-10.

- Spano N. Vulvodinia. 2010. Cuem ed.

- Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Yolken RH, editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 8th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 2003.

- Core R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria). URL https://www.R-project.org/. 2015.

- Savard M. Bridging the communication gap between physicians and their patients with physical symptoms of depression. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6(Suppl 1):17-24.

pubmed - De Oliveira JF. The effect of the internet on the patient-doctor relationship in a hospital in the city of Sao Paulo. JISTEM. 2014;11(2):327-344.

doi - Palmieri B, Laurino C, Vadala M. The "Second Opinion Medical Network". Int J Pathol and Clin Res. 2017;3(1):1-7.

- Palmieri B, Iannitti T, Capone S, Fistetto G, Arisi E. [Second opinion clinic: is the Web Babel Syndrome treatable?]. Clin Ter. 2011;162(6):575-583.

pubmed - Palmieri B, Iannitti T. The Web Babel syndrome. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):331-333.

doi pubmed - Di Cerbo A, Palmieri B. The economic impact of second opinion in pathology. Saudi Med J. 2012;33(10):1051-1052.

pubmed - Tommola P, Unkila-Kallio L, Paetau A, Meri S, Kalso E, Paavonen J. Immune activation enhances epithelial nerve growth in provoked vestibulodynia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6):768 e761-768 e768.

- Donders G, Bellen G, Rezeberga D. Aerobic vaginitis in pregnancy. BJOG. 2011;118(10):1163-1170.

doi pubmed - Mirowski GW, Schlosser BJ, Stika CS. Cutaneous vulvar streptococcal infection. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16(3):281-284.

doi pubmed - Ventolini G, Gygax SE, Adelson ME, Cool DR. Vulvodynia and fungal association: a preliminary report. Med Hypotheses. 2013;81(2):228-230.

doi pubmed - Farmer MA, Taylor AM, Bailey AL, Tuttle AH, MacIntyre LC, Milagrosa ZE, Crissman HP, et al. Repeated vulvovaginal fungal infections cause persistent pain in a mouse model of vulvodynia. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(101):101ra191.

doi pubmed - Simoes JA, Aroutcheva A, Heimler I, Shott S, Faro S. Bacteriocin susceptibility of Gardnerella vaginalis and its relationship to biotype, genotype, and metronidazole susceptibility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(5):1186-1190.

doi pubmed - Mastromarino P, Brigidi P, Macchia S, Maggi L, Pirovano F, Trinchieri V, Conte U, et al. Characterization and selection of vaginal Lactobacillus strains for the preparation of vaginal tablets. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;93(5):884-893.

doi pubmed - Boris S, Suarez JE, Vazquez F, Barbes C. Adherence of human vaginal lactobacilli to vaginal epithelial cells and interaction with uropathogens. Infect Immun. 1998;66(5):1985-1989.

pubmed - Cauci S, Guaschino S, De Aloysio D, Driussi S, De Santo D, Penacchioni P, Quadrifoglio F. Interrelationships of interleukin-8 with interleukin-1beta and neutrophils in vaginal fluid of healthy and bacterial vaginosis positive women. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9(1):53-58.

doi pubmed - Palmieri B, Benuzzi G, Bondi M. Carbossiterapia e irrigazioni vaginali: report clinico. Gazz Med Italiana. 2003;162(6):133-140.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.