| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Case Report

Volume 8, Number 11, November 2016, pages 824-830

Primary B-Cell Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma of the Hard Palate and Parotid Gland: Report of One Case and Review of the Literature

Ipek Yonal-Hindilerdena, e, Fehmi Hindilerdenb, Serkan Arslanc, Nalan Turan-Guzeld, Ibrahim Oner Dogand, Meliha Nalcacia

aDivision of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, Istanbul University Istanbul Medical Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey

bHematology Clinic, Istanbul Bakirkoy Sadi Konuk Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

cRadiology Clinic, Istanbul Bakirkoy Sadi Konuk Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

dDepartment of Pathology, Istanbul University Istanbul Medical Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey

eCorresponding Author: Ipek Yonal-Hindilerden, Division of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, Istanbul University Istanbul Medical Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey

Manuscript accepted for publication September 07, 2016

Short title: Primary B-Cell MALT Lymphoma

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jocmr2733w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

A 61-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with an ulcerated palate mass and swelling of the right parotid gland. Incisional biopsy from the hard palate revealed an extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, also called mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Final diagnosis was MALT lymphoma of the parotid gland with concomitant involvement of an extremely seldom site of involvement: the hard palate. To our knowledge, this report illustrates the first case of MALT lymphoma of the hard palate and parotid gland without an underlying autoimmune disease. Rituximab-based combination regimen (R-CHOP) provided complete remission with total regression of mass lesions at the hard palate and parotid gland. At 44-month follow-up, there is no disease relapse. We adressed the manifestations and management of MALT lymphoma patients with involvement of salivary gland and oral cavity.

Keywords: MALT lymphoma; Hard palate; Parotid gland

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) is an indolent B-cell lymphoma that accounts for about 5-17% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHLs) in adults [1]. MZL arises from post-germinal center marginal zone B cells present in lymph nodes and extranodal tissues. The neoplastic cells share a similar immunophenotype: positive for B-cell markers CD19, CD20, and CD22, and negative for CD5, CD10, and usually CD23 [2-4]. According to the REAL/WHO classification systems, MZL comprises three subtypes: extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, also called mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (NMZL) and splenic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (SMZL) (± villous lymphocytes). MALT lymphomas are the most common type of MZL, which constitute about 5% of all NHLs [5]. MALT lymphomas are divided into gastric and non-gastric MALT lymphomas based on the localization at initial diagnosis. The most common manifestation sites of non-gastric MALT lymphomas are the salivary glands, the thyroid, the upper airways, the lung, the ocular adnexa, the breast, the liver, the urothelial system, the skin, the dura and other soft tissues [1]. In the head and neck region except for the salivary glands, the development of this neoplasm is very rare [6]. Thus far, only few previous cases of MALT lymphoma with involvement of hard palate have been reported [6-14]. Herein, we report on a case of MALT lymphoma of the parotid gland with concomitant involvement of an extremely rare site of occurrence: the hard palate.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

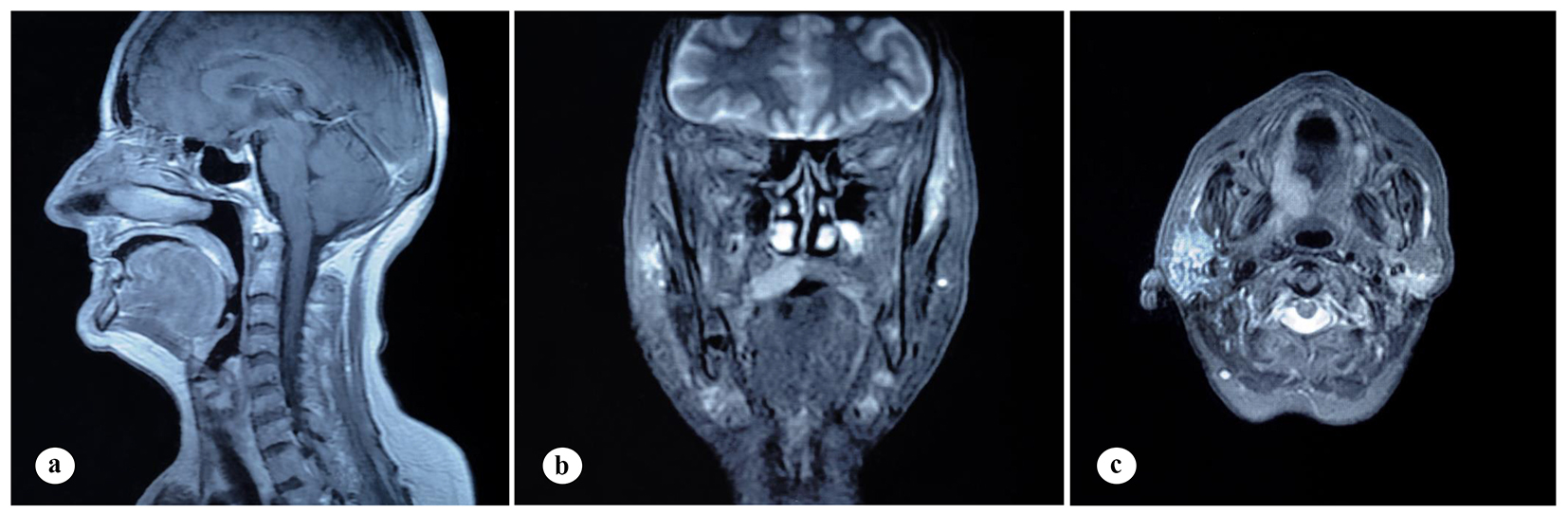

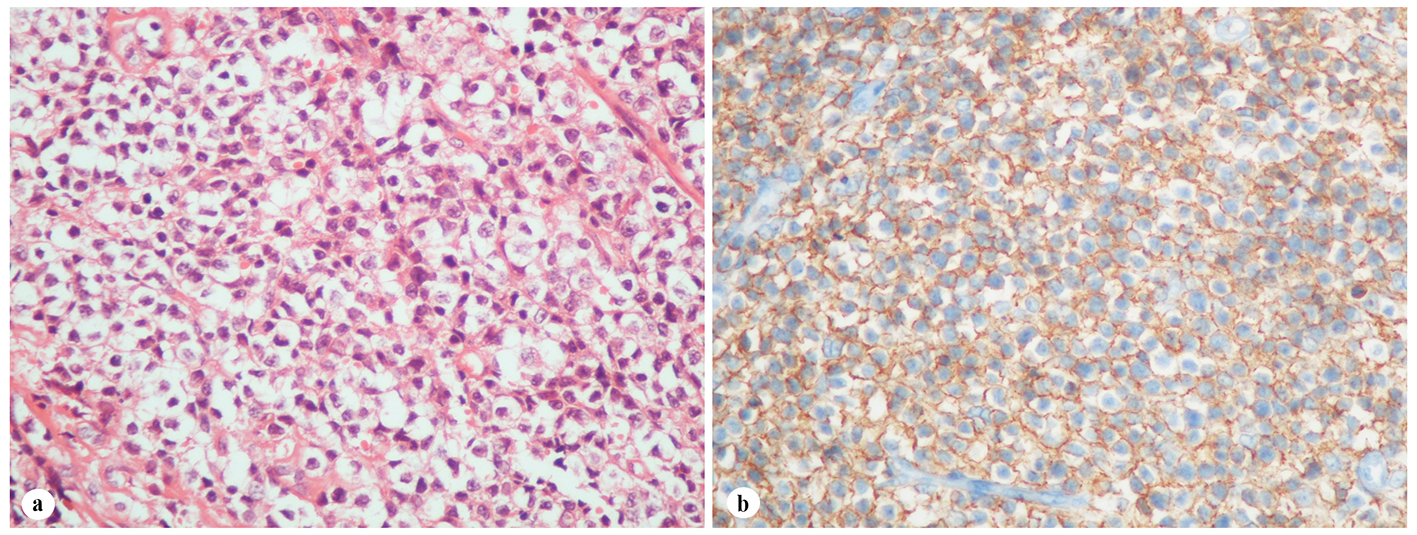

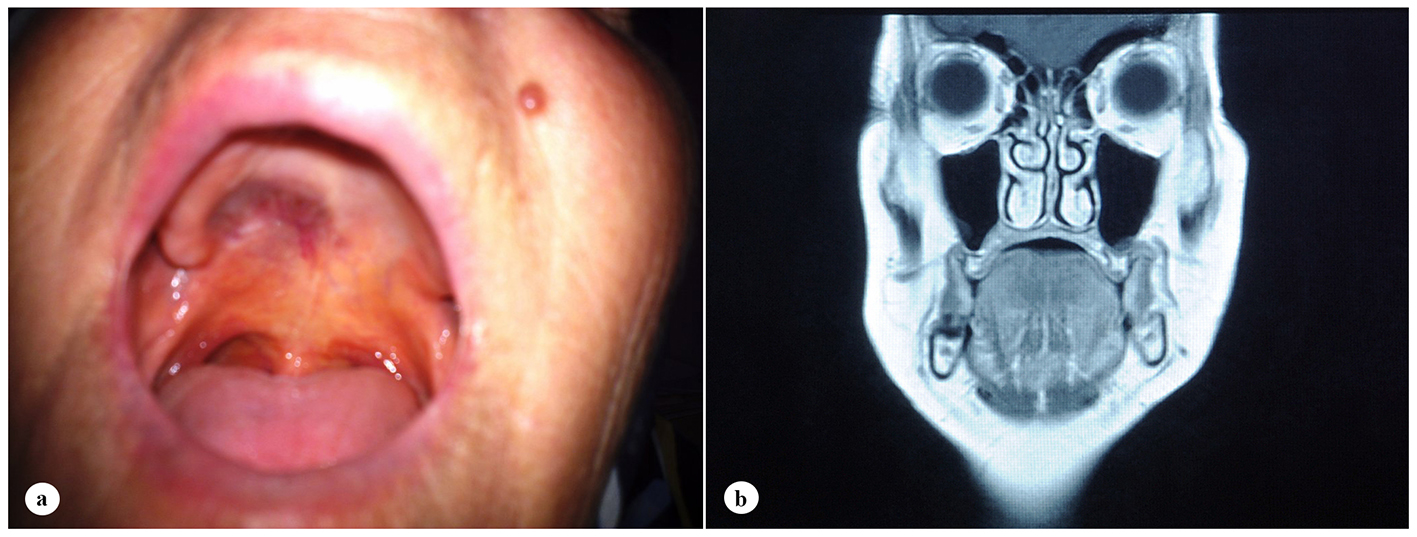

A 61-year-old woman was admitted to the Department of Otolaryngology with a 1-year history of swelling in the right palatal region and problems with pronunciation and chewing. Also, she suffered from a painless, progressively enlarging mass in the right preauricular region. On physical examination, swelling of the right parotid gland (Fig. 1a) and a 2 × 2.5 cm mass with central ulceration on the right hard palate (Fig. 1b) were noted. She had no history of fever, weight loss or night sweats. No lymph nodes were palpated in the head and neck region. Blood count was as follows: hemoglobin 13 g/dL, total leukocyte count 6,240/mm3 (neutrophil 54%, lymphocyte 36%) and platelet 185,000/mm3. Biochemical tests showed normal lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), beta-2 microglobulin levels and protein electrophoresis were normal. Cervical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed a 2 × 2.5 cm mass on the right side of the hard palate and a 2.5 × 3.5 cm mass in the right parotid gland region (Fig. 2a, b and c). Incisional biopsy of the palatal mass revealed subepithelial infiltration of atypical centrocyte-like cells with or without clear cytoplasm that stained for CD20 and kappa light chain, and did not stain for CD5, CD10, CD23 and lambda light chain, suggesting marginal zone B-cell lineage (Fig. 3a, b). Further examination included hepatitis B, C, HIV testing, chest and abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT), bone marrow aspirate and biopsy, and gastroscopy with multiple biopsies, all of which revealed unremarkable findings. The final diagnosis was MALT lymphoma with involvement of two extralymphatic sites: parotid gland and hard palate. Screening for autoimmune disorders including Sjogren’s syndrome was negative. Because of multiple extranodal involvements, a multi-agent chemotherapy regimen, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and methylprednisolone (R-CHOP) was started. After five cycles, the patient had improved quality of life through the recovery of orofacial functions such as pronunciation and chewing. After six cycles, mass arising from the right side of the hard palate almost totally disappeared and the ulceration totally regressed (Fig. 4a). Also, swelling on the right parotid gland significantly regressed. MRI confirmed the disappereance of the mass in the right palatal region (Fig. 4b) and the marked regression of the enlargement of the right parotid gland. Chemotherapy was completed up to eight cycles. She has been in complete remission (CR) without any evidence of recurrent lymphoma infiltration for the past 44 months.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Clinical features of the patient at admission. (a) Swelling of the right parotid gland. (b) A 2 × 2.5 cm mass with central ulceration on the right hard palate. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Findings on cervical MRI. (a) Isointense mass lesion on the hard palate on sagittal, T1-weighted plane. (b) Mass lesion on the right side of the hard palate on coronal, T1-weighted, fat-saturated, contrast-enhanced sequence. (c) Mass lesion in the right parotid gland on axial, T1-weighted, contrast-enhanced plane. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Histopathological findings of the palatal mass. (a) Subepithelial infiltration of atypical centrocyte-like cells with or without clear cytoplasm (H&E stain, × 400). (b) Infiltrated cells in the hard palate with CD20 expression (H&E stain, × 400). |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Case image and clinical findings after six cycles of chemotherapy. (a) Total regression of the ulcerated mass on the right hard palate. (b) Disappearance of the mass at the right palatal region on T1-weighted coronal MRI. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

MZL is a rare type of NHL characterized by indolent nature with three subgroups: MALT lymphoma, NMZL and SMZL. A variety of factors including chronic infections (e.g. Helicobacter pylori, HCV, Campylobacter jejuni, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Chlamydia psittaci) and autoimmune diseases (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus and Wegener’s granulomatosis) have been reported to be associated with MZL [1]. MALT lymphomas are the most common subgroup of MZL and also account for a significant proportion of extranodal lymphomas [5, 6]. Isaacson and Wright in 1983 first described MALT lymphoma as a low grade B-cell lymphoma [15]. For MALT lymphomas, average age at diagnosis is 60 years with a slight female predominance [16]. MALT lymphomas occur most commonly in stomach and they can be found virtually in every organ including the intestine, salivary glands, thyroid, lung and orbit, and also though less frequently, the skin, urinary bladder and the gonads [17].

NHLs of the salivary gland account for only 1.7% of salivary gland malignancies [18]. Salivary gland NHL comprises 4% of all NHLs and 4.7% of extranodal NHLs [19, 20]. The most frequently involved gland is the parotid gland, followed by submandibular gland, minor salivary glands and sublingual glands [18, 19, 21-23]. MALT lymphoma is the most common type of NHL of the salivary gland [9, 23]. It was reported that MALT lymphoma very rarely develops in the head and neck region except for the salivary glands [6]. For MALT lymphomas, the second most common site of involvement following the stomach is the salivary gland [24]. In the present case, one of the involved extranodal sites is the parotid gland, an acknowledged location of MALT lymphoma.

Etiopathogenesis of MALT lymphomas is not fully understood. MALT lymphomas are usually associated with chronic antigenic stimulation triggered by persistent infections and/or autoimmune processes [1]. Wotherspoon et al suggested that Helicobacter pylori-associated chronic gastric inflammation may induce gastric MALT lymphoma [25]. Kahl and Yang reported that H. pylori infection is present in 90% of gastric MALT lymphoma cases [26]. There are also several reports implicating infectious agents and autoimmune diseases in the pathogenesis of certain nongastric MALT lymphomas [1, 27-30]. Most salivary gland MALT lymphomas are thought to develop on the basis of chronic antigenic stimulation in the presence of Sjogren’s syndrome [28-33]. Our patient had parotid gland involvement, but showed no sign of autoimmune disease neither at diagnosis nor during the disease course.

Primary lymphomas of the oral cavity are rare [34]. In approximately 2% of all extranodal lymphomas, the primary site of involvement is the oral cavity including the palate, gingiva, tongue, buccal mucosa, lips, and floor of the mouth [35]. Primary lymphomas of the oral cavity in non-immuncompromised patients most commonly present as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBL). Mantle cell lymphoma, MALT lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, lymphomablastic lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma and anaplastic large cell lymphoma have been reported as well [36]. Kemp et al evaluated 40 cases of oral cavity NHLs [37]. Most cases were of B-cell lineage (98%), the majority of which (58%) were histologically subtyped as DLBL, followed by follicular lymphoma (15%), MALT lymphoma (13%), plasma cell tumors (8%) and small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (5%) [37]. Sites of involvement included the upper jaw (maxilla or palatal bone) (28%), mandible (20%), palatal soft tissue (20%), vestibule and gingiva (17%), buccal mucosa (9%), floor of mouth (3%) and the lower lip (3%) [37]. The hard palate is an uncommon site of MALT lymphoma and to our knowledge, there are only several case reports of a similar case [6-14]. Tauber et al reported the first case of MALT lymphoma of the hard palate [6]. Clinical details of the patients diagnosed with MALT lymphoma of the hard palate in the literature including our case are summarized in Table 1 [6-14]. The described cases show a strong female predominance (9:1) and are mostly of older age. Four to seven percent of patients with Sjogren’s syndrome develop malignant B-cell lymphomas, 48-75% of which are MALT lymphomas [38, 39]. Sjogren’s syndrome plays a major role in the development of MALT lymphoma of the oral and maxillofacial region, most frequently being located in the parotid gland [40-42]. As depicted in Table 1, Sjogren’s syndrome was observed in one-third of MALT lymphoma patients with palatal involvement. Considering the importance of Sjogren’s syndrome, we screened and ruled out autoimmune disorders in our patient. The most frequent clinical appearance of palatal MALT lymphomas is non-tender yet rarely ulcerated mass [8]. To our knowledge, only two previous reports described ulcerated masses associated with palatal MALT lymphomas [1, 7]. Our patient also presented with ulceration located at the center of the hard palate. She had multiple extranodal involvements, hard palate and parotid gland, as reported in the two other cases [4, 6]. Our patient had no underlying autoimmune disease in contrast to the two aferomentioned cases [4, 6]. MALT lymphoma in general is an indolent disease, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 86-95%. Patients with localized and disseminated disease show no significant difference in clinical course [24, 43]. The follow-up durations of MALT lymphoma patients with hard palate involvement were between 6 and 48 months; our case has the second longest follow-up duration (Table 1) [6-14]. One of the patients was lost to follow-up and one had succembed to the disease due to relapse. There is no optimal treatment for MALT lymphomas because of their relative infrequency and heterogeneity in disease biology, clinical presentation and behavior. In non-gastric MALT lymphomas with symptomatic local disease, local treatment (surgery or radiotherapy) results in excellent disease control [44]. For symptomatic disseminated disease, chemotherapy has commonly been used, with 75% CR rate and 5-year event-free survival and overall survival rates of 50% and 75%, respectively [24, 43, 45-47]. More recently, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab, which alone or in combination with chemotherapy demonstrated efficacy against B-cell lymphomas, has also been used effectively in MALT lymphomas [48-52]. Given the risk of occult disseminated disease, extensive workup procedures are needed in non-gastric MALT lymphomas including a staging system based on the Ann Arbor classification and the modification for primary gastric lymphoma by Musshoff [53, 54]. According to the aforementioned classification systems, patients were divided to three subgroups: localized disease, locally disseminated disease and disseminated disease. Since our patient had disseminated disease with involvement of multiple extranodal sites (hard palate and parotid gland), we administered rituximab-based chemotherapy. Of the other two reported disseminated MALT lymphomas with hard palate involvement, one was treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy and the other with rituximab (Table 1). All patients with localized disease except one were treated with surgical excision of the mass on the hard palate while the single patient experienced spontaneous regression of the tumor (Table 1). Cases of spontaneous regression of several MALT lymphoma of the rectum and ocular adnexa have been reported [55, 56]. Of the described palatal MALT lymphomas, one showed CR after the biopsy (Table 1) [12]. The mechanisms for spontaneous regression of tumors can be explained by several factors: immune mediation, tumor inhibition by growth factors and/or cytokines, induction of differentiation, elimination of carcinogens, tumor necrosis or angiogenesis inhibition, psychological factors, apoptosis and epigenetic mechanisms [57, 58]. In the above-mentioned case, Sakuma et al speculated that traumatic effect and localized infection induced by the surgical intervention might have activated tumor immunity and hence provided spontaneous regression [12].

Click to view | Table 1. Clinical Features of MALT Lymphoma With Hard Palate Involvement |

In conclusion, based on information synthesized from the literature review, extensive workup procedures, including history and physical examination, complete blood cell counts and basic biochemical studies including tests of renal and liver function, LDH and β2-microglobulin levels, protein electrophoresis; HIV, HCV, and HBV serologies; CT scans of the cervical region, chest, abdomen, and pelvis; bone marrow aspirate and biopsy; and gastroduodenal endoscopy with multiple biopsies to exclude a concomitant gastric involvement are mandatory in all MALT lymphomas because of the risk of occult disseminated disease. Current management guidelines recommend a “patient-tailored” approach taking into account the stage, site and clinical characteristics of the individual non-gastric MALT lymphoma patient. Therapeutic strategies for MALT lymphomas are not standardized due to the small number of cases described in the head and neck region. Herein, we described a rare MALT lymphoma patient of the hard palate with concomitant parotid gland involvement, who remained disease free for 44 months. In case of multiorgan involvement, systemic therapy with either chemotherapy or chemotherapy in combination with rituximab seems to be an appropriate option for MALT lymphoma of the head and neck region.

| References | ▴Top |

- Joshi M, Sheikh H, Abbi K, Long S, Sharma K, Tulchinsky M, Epner E. Marginal zone lymphoma: old, new, targeted, and epigenetic therapies. Ther Adv Hematol. 2012;3(5):275-290.

doi pubmed - Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, Banks PM, Chan JK, Cleary ML, Delsol G, et al. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84(5):1361-1392.

pubmed - Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, Flandrin G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Vardiman J, Lister TA, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(12):3835-3849.

pubmed - Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL (Eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC Press, Lyon. 2008.

- Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD. New approach to classifying non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: clinical features of the major histologic subtypes. Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(8):2780-2795.

pubmed - Tauber S, Nerlich A, Lang S. MALT lymphoma of the paranasal sinuses and the hard palate: report of two cases and review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263(1):19-22.

doi pubmed - Ayers LS, Oxenberg J, Zwillenberg S, Ghaderi M. Marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma of the bony palate presenting as sinusitis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008;87(1):36-38.

pubmed - Manveen JK, Subramanyam R, Harshaminder G, Madhu S, Narula R. Primary B-cell MALT lymphoma of the palate: A case report and distinction from benign lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma). J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16(1):97-102.

doi pubmed - Dunn P, Kuo TT, Shih LY, Lin TL, Wang PN, Kuo MC, Tang CC. Primary salivary gland lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 23 cases in Taiwan. Acta Haematol. 2004;112(4):203-208.

doi pubmed - Kolokotronis A, Konstantinou N, Christakis I, Papadimitriou P, Matiakis A, Zaraboukas T, Antoniades D. Localized B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of oral cavity and maxillofacial region: a clinical study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99(3):303-310.

doi pubmed - Pijpe J, van Imhoff GW, Vissink A, van der Wal JE, Kluin PM, Spijkervet FK, Kallenberg CG, et al. Changes in salivary gland immunohistology and function after rituximab monotherapy in a patient with Sjogren's syndrome and associated MALT lymphoma. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(6):958-960.

doi pubmed - Sakuma H, Okabe M, Yokoi M, Eimoto T, Inagaki H. Spontaneous regression of intraoral mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: molecular study of a case. Pathol Int. 2006;56(6):331-335.

doi pubmed - Shah AK, Gabhane MH, Kulkarni M. Primary extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of hard palate: a case report. Int J Case Rep. Images. 2012;3(5):21-24.

doi - Abe S, Yokomizo N, Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto K. Confirmation of immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement by polymerase chain reaction using surgically obtained, paraffin-embedded samples to diagnose primary palate mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: A case study. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;10:129-133.

doi pubmed - Isaacson P, Wright DH. Malignant lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. A distinctive type of B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 1983;52(8):1410-1416.

doi - Lymphoma: Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment (Cambridge Medicine). Cambridge University Press. ISBN:1107010594.

- Raderer M, Vorbeck F, Formanek M, Osterreicher C, Valencak J, Penz M, Kornek G, et al. Importance of extensive staging in patients with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)-type lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2000;83(4):454-457.

doi pubmed - Gleeson MJ, Bennett MH, Cawson RA. Lymphomas of salivary glands. Cancer. 1986;58(3):699-704.

doi - Schusterman MA, Granick MS, Erickson ER, Newton ED, Hanna DC, Bragdon RW. Lymphoma presenting as a salivary gland mass. Head Neck Surg. 1988;10(6):411-415.

doi pubmed - Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer. 1972;29(1):252-260.

doi - Hyman GA, Wolff M. Malignant lymphomas of the salivary glands. Review of the literature and report of 33 new cases, including four cases associated with the lymphoepithelial lesion. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976;65(4):421-438.

doi - Takahashi H, Tsuda N, Tezuka F, Fujita S, Okabe H. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the major salivary gland: a morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 15 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1990;19(7):306-312.

doi pubmed - Wolvius EB, van der Valk P, van der Wal JE, van Diest PJ, Huijgens PC, van der Waal I, Snow GB. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the salivary glands. An analysis of 22 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25(4):177-181.

doi pubmed - Zucca E, Conconi A, Pedrinis E, Cortelazzo S, Motta T, Gospodarowicz MK, Patterson BJ, et al. Nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Blood. 2003;101(7):2489-2495.

doi pubmed - Wotherspoon AC, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon MR, Isaacson PG. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet. 1991;338(8776):1175-1176.

doi - Kahl B, Yang D. Marginal zone lymphomas: management of nodal, splenic, and MALT NHL. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008:359-364.

doi pubmed - Guidoboni M, Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Doglioni C, Dolcetti R. Infectious agents in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-type lymphomas: pathogenic role and therapeutic perspectives. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2006;6(4):289-300.

doi pubmed - Hyjek E, Smith WJ, Isaacson PG. Primary B-cell lymphoma of salivary glands and its relationship to myoepithelial sialadenitis. Hum Pathol. 1988;19(7):766-776.

doi - Schmid U, Lennert K, Gloor F. Immunosialadenitis (Sjogren's syndrome) and lymphoproliferation. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1989;7(2):145-180.

- Falzon M, Isaacson PG. The natural history of benign lymphoepithelial lesion of the salivary gland in which there is a monoclonal population of B cells. A report of two cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15(1):59-65.

doi pubmed - Muller-Hermelink HK, Greiner A. [Autoimmune diseases and malignant lymphoma]. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 1992;76:96-109.

pubmed - Ihrler S, Baretton GB, Menauer F, Blasenbreu-Vogt S, Lohrs U. Sjogren's syndrome and MALT lymphomas of salivary glands: a DNA-cytometric and interphase-cytogenetic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13(1):4-12.

doi pubmed - Zucca E, Gregorini A, Cavalli F. Management of non-Hodgkin lymphomas arising at extranodal sites. Ther Umsch. 2010;67(10):517-525.

doi pubmed - Jonsson MV, Theander E, Jonsson R. Predictors for the development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Presse Med. 2012;41(9 Pt 2):e511-516.

doi pubmed - Solans-Laque R, Lopez-Hernandez A, Bosch-Gil JA, Palacios A, Campillo M, Vilardell-Tarres M. Risk, predictors, and clinical characteristics of lymphoma development in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41(3):415-423.

doi pubmed - Hicks MJ, Flaitz CM. External root resorption of a primary molar: "incidental" histopathologic finding of clinical significance. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92(1):4-8.

doi pubmed - Kemp S, Gallagher G, Kabani S, Noonan V, O'Hara C. Oral non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: review of the literature and World Health Organization classification with reference to 40 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105(2):194-201.

doi pubmed - Sutcliffe N, Inanc M, Speight P, Isenberg D. Predictors of lymphoma development in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1998;28(2):80-87.

doi - Theander E, Henriksson G, Ljungberg O, Mandl T, Manthorpe R, Jacobsson LT. Lymphoma and other malignancies in primary Sjogren's syndrome: a cohort study on cancer incidence and lymphoma predictors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(6):796-803.

doi pubmed - Kassan SS, Thomas TL, Moutsopoulos HM, Hoover R, Kimberly RP, Budman DR, Costa J, et al. Increased risk of lymphoma in sicca syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(6):888-892.

doi pubmed - Tzioufas AG, Boumba DS, Skopouli FN, Moutsopoulos HM. Mixed monoclonal cryoglobulinemia and monoclonal rheumatoid factor cross-reactive idiotypes as predictive factors for the development of lymphoma in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(5):767-772.

doi pubmed - Voulgarelis M, Dafni UG, Isenberg DA, Moutsopoulos HM. Malignant lymphoma in primary Sjogren's syndrome: a multicenter, retrospective, clinical study by the European Concerted Action on Sjogren's Syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(8):1765-1772.

doi - Thieblemont C, Berger F, Dumontet C, Moullet I, Bouafia F, Felman P, Salles G, et al. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma is a disseminated disease in one third of 158 patients analyzed. Blood. 2000;95(3):802-806.

pubmed - Thieblemont C. Clinical presentation and management of marginal zone lymphomas. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005:307-313.

doi pubmed - Hammel P, Haioun C, Chaumette MT, Gaulard P, Divine M, Reyes F, Delchier JC. Efficacy of single-agent chemotherapy in low-grade B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma with prominent gastric expression. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(10):2524-2529.

pubmed - Thieblemont C, de la Fouchardiere A, Coiffier B. Nongastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas. Clin Lymphoma. 2003;3(4):212-224.

doi pubmed - Zinzani PL, Magagnoli M, Galieni P, Martelli M, Poletti V, Zaja F, Molica S, et al. Nongastrointestinal low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: analysis of 75 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(4):1254.

pubmed - Maloney DG, Grillo-Lopez AJ, White CA, Bodkin D, Schilder RJ, Neidhart JA, Janakiraman N, et al. IDEC-C2B8 (Rituximab) anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in patients with relapsed low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood. 1997;90(6):2188-2195.

pubmed - Conconi A, Martinelli G, Thieblemont C, Ferreri AJ, Devizzi L, Peccatori F, Ponzoni M, et al. Clinical activity of rituximab in extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type. Blood. 2003;102(8):2741-2745.

doi pubmed - Martinelli G, Laszlo D, Ferreri AJ, Pruneri G, Ponzoni M, Conconi A, Crosta C, et al. Clinical activity of rituximab in gastric marginal zone non-Hodgkin's lymphoma resistant to or not eligible for anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):1979-1983.

doi pubmed - Nuckel H, Meller D, Steuhl KP, Duhrsen U. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in relapsed MALT lymphoma of the conjunctiva. Eur J Haematol. 2004;73(4):258-262.

doi pubmed - Raderer M, Jager G, Brugger S, Puspok A, Fiebiger W, Drach J, Wotherspoon A, et al. Rituximab for treatment of advanced extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Oncology. 2003;65(4):306-310.

doi pubmed - Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, Glatstein E, Canellos GP, Young RC, Rosenberg SA, et al. Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin's disease: Cotswolds meeting. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7(11):1630-1636.

pubmed - Musshoff K. [Clinical staging classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (author's transl)]. Strahlentherapie. 1977;153(4):218-221.

pubmed - Okamura S, Katsuhiko H, Satoh T. Regression of rectal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma unrelated to Helicobacter pylori. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):247.

doi pubmed - Matsuo T, Sato Y, Kuroda R, Matsuo N, Yoshino T. Systemic malignant lymphoma 17 years after bilateral orbital pseudotumor. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2004;48(5):503-506.

doi pubmed - Drobyski WR, Qazi R. Spontaneous regression in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: clinical and pathogenetic considerations. Am J Hematol. 1989;31(2):138-141.

doi - Papac RJ. Spontaneous regression of cancer: possible mechanisms. In Vivo. 1998;12(6):571-578.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.