| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Original Article

Volume 6, Number 3, June 2014, pages 173-183

The Impact of a Heart Failure Educational Program for Physicians Varies Based Upon Physician Specialty

Linda G. Parka, e, Denis Maharb, Richard E. Shawc, Kathleen Dracupd

aSan Francisco VA Medical Center, 4150 Clement Street 181G, San Francisco, CA 94121, USA

bContra Costa Regional Medical Center, 2500 Alhambra Ave, Martinez, CA 94553, USA

cCalifornia Pacific Medical Center, 2200 Webster St, San Francisco, CA 94115, USA

dDepartment of Physiological Nursing, University of California, 2 Koret Way, N611, San Francisco, CA 94143, USA

eCorresponding author: Linda G. Park, Division of Geriatrics, University of California, San Francisco VA Medical Center, 4150 Clement Street 181G, San Francisco, CA 94121, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication March 13, 2014

Short title: Heart Failure Educational Program

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr1790w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Beta blocker (BB) doses are often suboptimal in heart failure (HF) management. Differences in BB management patterns may exist between physicians in family medicine (FM) and internal medicine (IM). The aims of this study were to compare: 1) BB doses and prescription patterns; and 2) health care utilization rates in patients cared for by all primary care physicians compared to an historical control group after an educational program on HF management. A subgroup analysis was performed between patients cared for by FM and IM physicians. A secondary aim was to assess physician knowledge scores and satisfaction.

Methods: A historically controlled study was conducted among low-income, underserved HF patients (mean age 54.1 ± 13.1, males 70%, mean ejection fraction 28.2 ± 9.8%). Statistical methods included linear mixed models and Fisher’s exact tests to assess prescription patterns of BB dosing and health care utilization rates (all cause and HF related hospitalizations, emergency department use and clinic visits).

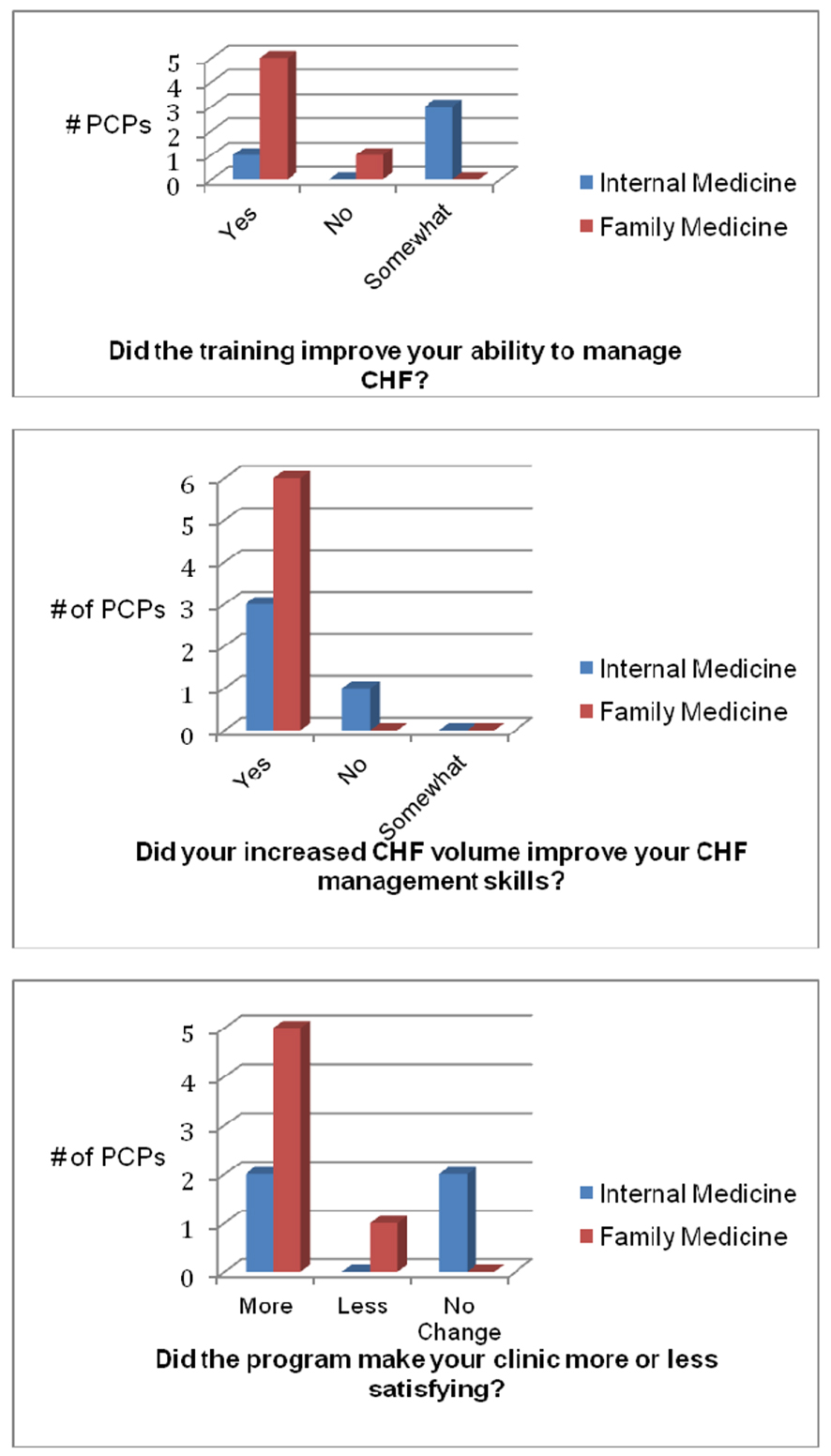

Results: Among 135 patients (experimental N = 81 and control N = 54), a linear mixed model test of group by time interaction showed no difference in BB dosage (t = -0.12, P = 0.91). FM physicians prescribed significant changes in BB doses compared to IM physicians (P = 0.04), had higher numbers of clinic visits (P = 0.03) and reported greater satisfaction with the program.

Conclusions: There was no difference in BB titration rates following an HF training intervention for physicians compared to historical controls. However, FM physicians had a greater change in prescribing practices compared to IM physicians. Educational programs targeting FM physicians may benefit HF patients and could potentially lead to greater adherence to clinical guidelines related to BB use and address gaps in providing HF care.

Keywords: Heart failure; Beta blocker; Primary care physician; Internal medicine; Family medicine; Practice variation; Education

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Reinforcement of evidence-based guidelines of heart failure (HF) remains an opportunity for continued professional development among practitioners who manage HF. HF is a complex clinical syndrome that requires a multifaceted therapeutic regimen and is associated with frequent hospitalizations, poor quality of life, high morbidity and 1-year mortality rates of up to 30% [1, 2]. Hospitalization and mortality rates vary substantially among geographic locations, representing marked differences in outcomes that are not explained by insurance status [2]. HF is the most common hospital discharge diagnosis among Medicare beneficiaries and is considered one of the most expensive conditions in the healthcare system due to frequent readmissions [3].

Among the availability of many therapeutic options for HF, the guidelines are clear about the recommendation for use of evidence-based medications such as beta blockers (BBs) to reduce morbidity and mortality in HF [1, 4]. Since the formal recommendation for BB use in the late 1990s, there was a slow uptake of prescribing appropriate dosage by practitioners, which was partly attributed to the previous contraindication of BB as HF therapy [5]. Over time, there has been a significant increase in BB use in the HF population, largely credited to campaigns and interventions stressing the practice statements of BB use and performance measures at hospitals with strict criteria for documented BB prescription [5-8].

BB doses are often prescribed at suboptimal levels [5, 8], which may not provide maximum benefit for HF patients. Reasons for inability to achieve maximum dosage may be related to adverse clinical response (for example, bradycardia, hypotension), adverse clinical symptoms (for example, fatigue) and exacerbation of comorbid conditions (for example, bronchospasm). However, other differences in BB management patterns may exist between physician groups due to differences in specialty interest and training. Studies have shown that HF patients treated by cardiologists have better clinical outcomes including adherence to treatments as well as reduced mortality and rehospitalization rates compared to HF patients who are treated by non-cardiologists [9-12].

HF patients are often treated by primary care physicians (PCPs), including physicians with specialties in family medicine (FM) and internal medicine (IM). There are limited data available about the impact of specialized HF training for PCPs and limited understanding about the differences in practice patterns of HF management between FM and IM physicians. Researchers who studied the predictors of increased prescription of BB by PCPs found physicians who were more confident about their knowledge of appropriate HF management had higher BB prescription rates [13]. Further research was recommended to study the impact of physician training and education on prescription patterns [13].

Therefore, we conducted a pilot study termed Specialty Training and Resources for Improved Outcomes and Adherence to National Guidelines in Congestive Heart Failure (STRONG CHF) directed at PCPs. The aims of this study were to examine the impact of a 1-day educational program by comparing: 1) BB doses and prescription patterns between HF patients who were treated by PCPs before and after the program; and 2) health care utilization rates with hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) use and clinic visits between groups. A subgroup analysis of BB doses, BB prescription patterns and health care utilization between FM and IM patients before and after the educational program was performed. A secondary aim was to assess PCP knowledge scores and satisfaction with the program.

| Methods | ▴Top |

Setting and participants

A historically controlled study [14] was conducted at a community, county hospital system in Northern California servicing a multiethnic population of low income, uninsured, underserved HF patients. This county hospital system had a limited number of specialty physicians and did not employ any cardiologists at the time of the program. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Contra Costa Regional Medical Center. Written informed consents were not deemed necessary as the protocol required data acquisition from an established database of electronic and paper medical records without patient contact.

The intervention was considered a pilot study to determine feasibility and acceptability, thus a power analysis and sample size calculation were not conducted a priori. All subjects in this sample were abstracted from a database of patients who were seen in one of six community-based clinics by the participating PCPs for a diagnosis of HF or cardiomyopathy. Data on BB doses and prescription practices were collected over a period of 14 months after the educational program for the experimental group (December 2009 to January 2011). The same data were collected for the control group who were seen by the trained PCPs for up to 23 months before the educational program (January 2008 to November 2009).

Patients were included for analysis if they had two or more clinic visits within 6 months with one of the trained PCPs, had left ventricular systolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction of ≤ 45% and were prescribed an evidence-based BB (or metoprolol tartrate). Although immediate release metoprolol tartrate is not considered an evidence-based BB for HF therapy [4], it was included in the analysis as it was often prescribed in lieu of sustained release metoprolol succinate because the latter was more costly in the hospital system. Patients who were previously taking BBs or had newly prescribed BBs were included in the analysis. Patients who were taking other BBs such as propanolol or atenolol were excluded.

Intervention

Twelve participating PCPs, including five FM and seven IM physicians, who were all employed by the county health system, participated in the same educational program. During the 6-h educational training session, HF specialists instructed PCPs on the fundamentals of HF management and used case-based studies that emphasized appropriate BB dosing based on current guideline recommendations.

Health systems changes were implemented to support the STRONG CHF project in following HF patients in a more timely manner by the trained providers. One dedicated HF visit slot was reserved in each PCP’s continuity clinic. A standard clinic note template was created for HF patients who were seen by these providers. Follow-up visits focused on HF symptom management plus timely and efficient medication dosing. Patients in this study continued to receive primary care services from their established PCP.

Outcomes

BB doses were compared between patients before and after physicians participated in the educational program in order to answer the major aim of the study. In addition, BB prescription patterns were compared in the following six categories: 1) dose unchanged, 2) up-titrated to maximum dose, 3) up-titrated but did not reach maximum dose, 4) already at maximum dose, 5) was at maximum dose then decreased, and 6) was not at maximum dose then decreased dose. Equivalency doses were established across different BBs, which allowed direct comparison. Data on a subgroup analysis detecting differences in BB doses and prescribing patterns between specialties were obtained.

To answer the next major aim, health care utilization rates were gathered on the number of all cause and HF related hospitalizations, ED use and clinic visits. Data on health care utilization were generally limited to services within the county health system unless physician records reported use at other medical institutions. A subgroup analysis on health care utilization was also performed between specialties.

For the secondary aim, surveys were administered to the participating PCPs to assess knowledge before and after the educational program. A survey about PCP satisfaction with the program was sent after the prospective study data were collected.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and clinical variables were compared between groups using t tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. A linear mixed model examined differences in BB dose between the experimental and control groups and was employed to detect change over time with consideration to missing data using SPSS 18.0 (Chicago, IL). The basic design has one between participants (fixed) factor, group, with two levels (experimental and control) and measures of BB dose change for up to seven clinic visits. Differences in BB prescription patterns were compared using Fisher’s exact test analyses. Similar statistical applications for BB management were performed between FM and IM physicians for the specialty subgroup analysis. Fisher’s exact tests were used to detect differences in health care utilization rates between the study groups.

| Results | ▴Top |

Study participants

The selection of study participants and groups compared are visually represented in Fig. 1. Medical records of historical control patients who received care from the participating PCPs 2 years prior to the intervention (N = 54) were compared to patients cared for following the educational program (N = 81). No sociodemographic or clinical differences were noted between experimental and control patients treated before or after the program (P > 0.05) (Table 1). The mean age of this sample was 54.1 ± 13.1 years, which is younger than typical HF patients because of the high incidence of illicit drug use among this group of patients (39%). Other key participant characteristics included a mean ejection fraction of 28.2 ± 9.8 and mean serum creatinine of 1.5 ± 1.0.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Groups identified and analyzed. BB: beta blocker; CV: clinic visits; FM: family medicine; HF: heart failure; IM: internal medicine; PCP: primary care physician. *Subgroup analysis compared IM and FM experimental groups. **Subgroup analysis compared IM and FM control groups. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The HF educational program did not result in significantly higher BB dose change or improved BB prescription patterns by PCPs. BB doses were suboptimal for HF patients, although the clinical reasons for restricting maximal dosage were not explored in this study. Importantly, a subgroup analysis showed the educational program on HF topics was shown to benefit HF patients in achieving significant BB dose change in FM physicians compared to IM physicians. However, a comparison between specific BB prescription patterns (for example, up-titration to maximum dose) between patients cared for before and after the educational program did not reveal any differences.

Health care utilization between the experimental and control groups was not significantly different, although there was a trend that HF patients had more clinic visits following the educational program. The subgroup analysis between specialties showed FM patients had more clinic visits than IM patients after the educational program, which may coincide with the significant finding of BB dose change in the FM group.

Lastly, FM physicians reported more satisfaction and practice improvement from the educational program compared to the IM physicians. The reports of higher satisfaction may be important information to tailor future programs in this cohort of physicians.

Several limitations may apply in this pilot study. The small sample size may not have allowed for significant differences to be noted between the experimental and control groups. The results of this younger patient population with socioeconomic challenges and a higher incidence of illicit drug use may be significantly different from other HF populations who are older, more attentive to their health care needs and have better access to health care providers. Thus, the results may be difficult to generalize. The patient characteristics between FM and IM groups showed IM patients were older, which may have led to bias, although other clinical factors were not significantly different. In addition, due to the high demand of clinic appointments with the PCPs involved in this study, there may have been a significant delay in scheduling follow-up visits, which in turn caused a delay in time and dosage of BB titration. The medical and socioeconomic complexities of patients in this study may have attenuated the effects of the educational program. In the subgroup analysis, characteristics of PCPs were not explored a priori (for example, age, years of practice). The IM physicians may have been highly experienced in managing complex HF patients given the specialty limited care that was available in this county hospital setting; therefore, the educational program may not have been as salient for them as for other physician groups.

The impact of future educational programs on specialty topics such as HF management for PCPs should be examined further, particularly in resource limited settings. Given the growing population of older adults that will be treated for HF, specialized educational training of PCPs appears to be a simple, feasible and practical solution to offering HF services, particularly in resource limited areas. Trained FM or IM physicians could potentially fill gaps in HF care in resource limited settings such as public health care systems or rural areas. Future research can replicate the educational program in health care systems that have few cardiologists. Specialty care for uninsured and underinsured patients in the United States is in short supply [15]; therefore, health care institutions require efficient and sustainable systems founded upon well-trained PCPs. A unique and feasible practice model in which FM and IM physicians expand their scope of work to provide specialty care in HF clinics with an interdisciplinary team is necessary to meet the growing population of HF patients. This model would allow for cardiologists to serve as consultants for very complicated or advanced HF patients and would allow them time to manage other complex cardiac patients.

Previous research has shown BB doses are often suboptimal, but are higher in HF patients who are managed by a cardiology specialist or specialized HF disease management programs [16-18]. Future research comparing PCPs after a specialized educational program for BB management in HF patients with cardiologists or other specialized HF disease management programs will determine whether an educational program can achieve comparable outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the physicians who participated in this study as well the support of Contra Costa Regional Center and clinics.

Funding

California Healthcare Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

None to disclose.

| References | ▴Top |

- Heart Failure Society of America. Executive summary: HFSA 2010 comprehensive heart failure practice guidelines. J Card Fail. 2010;16(6):475-539.

- Chen J, Normand SL, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998-2008. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1669-1678.

pubmed - Andrews RM, Elixhauser A. The national hospital bill: Growth trends and 2005 update on the most expensive conditions by payer. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2007.

- Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M,

et al . 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119(14):e391-479.

pubmed - LaPointe NM, DeLong ER, Chen A, Hammill BG, Muhlbaier LH, Califf RM, Kramer JM. Multifaceted intervention to promote beta-blocker use in heart failure. Am Heart J. 2006;151(5):992-998.

pubmed - Fonarow GC. The Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE): opportunities to improve care of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;4(Suppl 7):S21-30.

pubmed - Ansari M, Shlipak MG, Heidenreich PA, Van Ostaeyen D, Pohl EC, Browner WS, Massie BM. Improving guideline adherence: a randomized trial evaluating strategies to increase beta-blocker use in heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107(22):2799-2804.

pubmed - Gheorghiade M, Albert NM, Curtis AB, Thomas Heywood, McBride ML, Inge PJ, Mehra MR,

et al . Medication dosing in outpatients with heart failure after implementation of a practice-based performance improvement intervention: findings from IMPROVE HF. Congest Heart Fail. 2012;18(1):9-17.

pubmed - Reis SE, Holubkov R, Edmundowicz D, McNamara DM, Zell KA, Detre KM, Feldman AM. Treatment of patients admitted to the hospital with congestive heart failure: specialty-related disparities in practice patterns and outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(3):733-738.

pubmed - Philbin EF, Weil HF, Erb TA, Jenkins PL. Cardiology or primary care for heart failure in the community setting: process of care and clinical outcomes. Chest. 1999;116(2):346-354.

pubmed - Philbin EF, Jenkins PL. Differences between patients with heart failure treated by cardiologists, internists, family physicians, and other physicians: analysis of a large, statewide database. Am Heart J. 2000;139(3):491-496.

pubmed - Auerbach AD, Hamel MB, Davis RB, Connors AF, Jr., Regueiro C, Desbiens N, Goldman L,

et al . Resource use and survival of patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure: differences in care by specialty of the attending physician. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):191-200.

pubmed - Sinha S, Schwartz MD, Qin A, Ross JS. Self-reported and actual beta-blocker prescribing for heart failure patients: physician predictors. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8522.

pubmed - Friedman LM, Furberg CD, DeMets DL (2010). Fundamentals of clinical trials (4th ed). New York: Springer; 2010:3-79.

- Cook NL, Hicks LS, O'Malley AJ, Keegan T, Guadagnoli E, Landon BE. Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(5):1459-1468.

pubmed - Massie BM, Shah NB. Evolving trends in the epidemiologic factors of heart failure: rationale for preventive strategies and comprehensive disease management. Am Heart J. 1997;133(6):703-712.

pubmed - Whellan DJ, Gaulden L, Gattis WA, Granger B, Russell SD, Blazing MA, Cuffe MS,

et al . The benefit of implementing a heart failure disease management program. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(18):2223-2228.

pubmed - Ojeda S, Anguita M, Delgado M, Atienza F, Rus C, Granados AL, Ridocci F,

et al . Short- and long-term results of a programme for the prevention of readmissions and mortality in patients with heart failure: are effects maintained after stopping the programme? Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(5):921-926.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.